As of Friday, April 7, there now stands an adequate memorial commemorating the one and only Bob Murphy— the late New York Mets radio announcer.

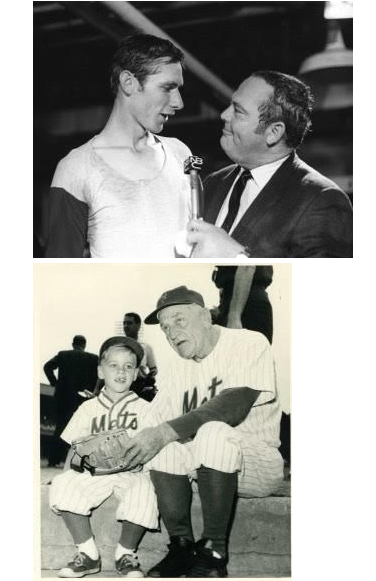

“It was a wonderful time for our family, for me and my sisters to be there,” Bob’s son Brian, a Kings Park resident raised in Huntington, told The Messenger in an interview on Wednesday. “We grew up as Mets fans. I have a picture of myself as a 5-year-old sitting with Casey Stengel on the top step of the dugout wearing a Mets uniform because it was family day. My whole life — I’ve been a Mets fan since I can remember.”

When the Mets took to the field for their first game in 1962, Bob Murphy took to the mic as the first Met broadcaster; a place he would stay for the next 40 years.

Murphy also worked for the Boston Red Sox and Baltimore Orioles prior to joining the Mets, and it was his call of Roger Maris’ 60th home run that helped land him the job with the organization.

After Murphy retired in 2003, he sadly passed away just a year later in 2004. A proper tribute was never really paid to him afterward, outside of a patch worn on the team’s jerseys that season.

When his broadcast partner Ralph Kiner died in 2014, he was given a tribute. Murphy’s former radio partner and current TV voice of the team, Gary Cohen, brought this fact up to current Met owner Steve Cohen. His response:

“I feel it’s totally appropriate that Ralph be honored that way; but, if so, Murph should be honored the same way.”

Cohen made a call to Murphy’s three children – Bob and daughters Kelly and Kasey – and told them they were invited to throw out first pitches at this year’s home opener and be a part of the ceremony to dedicate a Citi Field plaque to their father.

“Very exciting,” Kelly said. “Very thrilled, very honored. For us to have this honor, and to honor my dad like that, it’s so meaningful for all of us.”

Recounting the experience of throwing out the first pitch, Brian told The Messenger: “After the press conference we did before, [sports commentator] Keith Olbermann pulled us over and said, ‘just a little advice: if you throw it high, they’ll cheer. If you bounce it, they’ll boo.’”

Following some laughter, Brian added, “he then went on to tell us a story, that when my dad was in town, they’d have dinner every week. And he said, ‘you know, your father reminded me why I do this. He was just so enthusiastic about the sport and what he did.’”

Brian recalled bringing a transistor ham radio to Met games he watched in-person “just so I could still hear dad,” and that he was “able to go to bed [with the radio] when I was a kid and listen to my dad… I wish I could do it all over again.”

Murphy had a strong impact across the board as he guided Mets fans full of “Amazin’” pride far and wide — and in his own home – through the first four decades of their existence.

“He was always so positive about everything. Not only in the booth, but outside of the booth as well,” Kelly said. “When he said, ‘The sun is shining, the sky is blue, it’s a beautiful day for baseball,’ that was really who he was.”

The Mets would defeat the Miami Marlins 9-3 that afternoon to start off their season, much to the adoration of Mets fans in attendance, at home and listening in on the radio— the latter of which the Murphy children know more than any rely on in-the-moment descriptions their father was capable of delivering like no other.

Brian shared further with The Messenger: “the Mets’ new public relations director,” he recalled, “came up to us and told us my father had a special relationship with the blind people that were fans. They would come to the ballpark and say— ‘you paint the picture in my mind.’ And they were huge Mets fans also. My father was trying to be compassionate to everybody… he knew everybody, he was a very humble guy.” “To hear a story about my dad I had never heard before,” Brian said, “it was pretty awesome. And a lot of people approached us and told similar stories.”

Sure, there may be no crying in America’s pastime; but with a story like this, you can’t help but be romantic about baseball.