Few states wield as much political power as Pennsylvania does, especially in the Trump Era. It is on par with Rust Belt neighbors Wisconsin and Michigan for the longest active bellwether streak in the country, in that it sides with the general election winner. The Rust Belt trio have all done so since 2008.

But Pennsylvania has more predictive power than simply being a hotly-contested swing state that is guaranteed to have significant say in who becomes the next president. Being a swing state, and especially a bellwether, means that the state is microcosmic of the nation overall.

The reason is that Pennsylvania is now a microcosm of the country overall. Just as Ohio and Missouri each had culturally Northern and Southern regions, mixes of industry, agriculture, big cities, sprawling suburbs, and a healthy mix of working-class and educated populations, Pennsylvania now has the finger on the pulse of the American electorate. Dense, liberal cities with intensely progressive enclaves countered by ruby-red rural landscape dotted by working-class former steel towns, farms, and, even Amish communities make this a true amalgam of the American electorate. Moreover, its educated suburbs make for the ground-zero of any national campaign.

These reasons also show why Donald Trump’s margin, narrow as it was, is still indicative of a setback for Democrats’ electoral prospects.

Trump carried the commonwealth with 50.4% of the vote – a majority – to Kamala Harris’ (D-CA) 48.7% – a margin of about 1.7%, or 120,710 raw votes.

While a margin typical of a classic swing state, it’s the largest margin for a Republican candidate since George H. W. Bush (R-TX) won by 2.31% in 1988. Trump’s win is also seen to have aided down-ballot Republicans, such as Dave McCormick (R-PA) in flipping the U.S. Senate seat, as well as other statewide seats. Trump’s 3.5 million votes is a record for the most votes cast for any candidate in the history of the commonwealth. With almost seven million ballots cast, turnout was up slightly from 2020, at 76.6%.

For reference, Trump had won and flipped Pennsylvania in an upset in 2016, marking the first time the commonwealth would back the GOP since 1988. However, Trump’s narrow margin of just 0.72% – out of six million votes – was the narrowest margin in Pennsylvania in any presidential race since 1840. Despite this, 2016 marked the first time it had voted more Republican than the nation since 1948, a figure supported by Hillary Clinton’s (D-NY) two-point popular-vote win.

Trump’s key to victory then was essentially his key to victory now: appealing to working-class voters, especially those in economically depressed areas where industry had once reigned supreme, as well as suburbanites concerned about quality of life and crime.

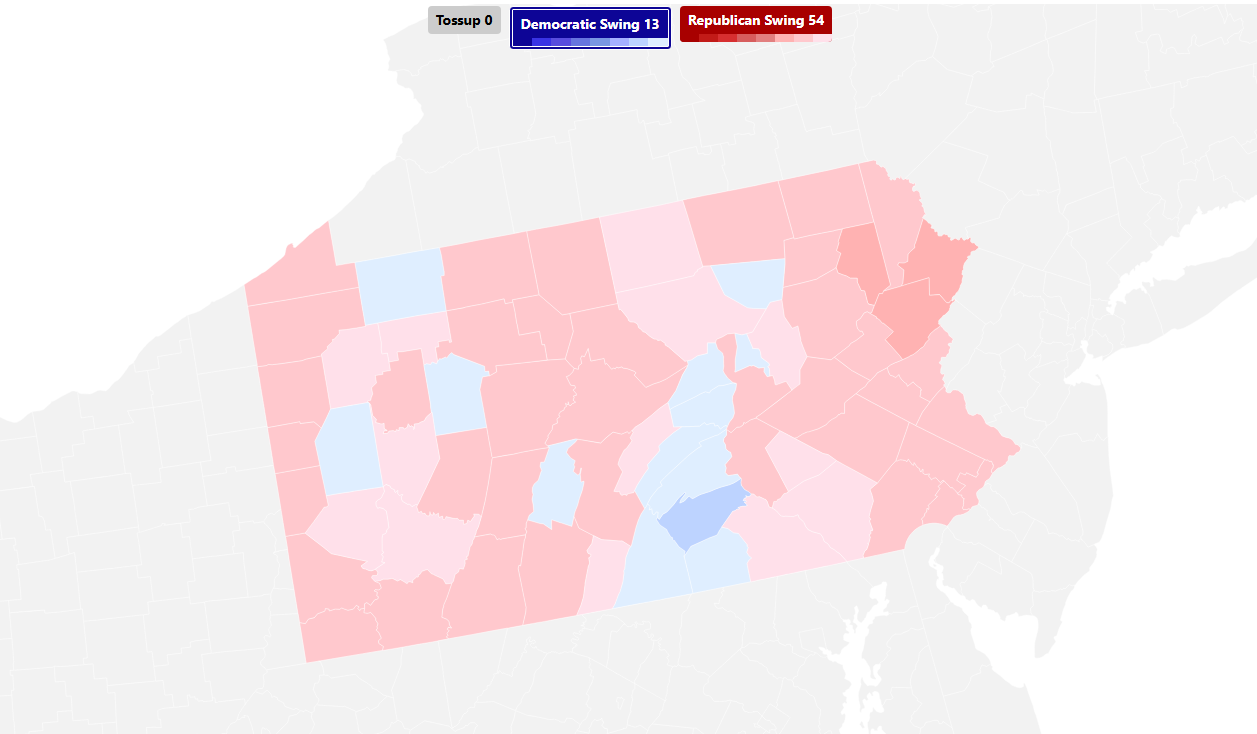

Trump flipped four counties, two of which had not backed him in 2016. He won the crucial bellwether of Erie County, as he did in 2016 but not in 2020; the case is similar in Northampton County, home to Bethlehem. Monroe County (Stroudsburg) and Bucks County (Bensalem) flipped to Trump after having not supported him in the prior two elections.

Philadelphia and the Collar Counties

Philadelphia, the nation’s sixth-largest city, has been a mainstay of the Democratic Party for generations. The consolidated city-county has not backed a Republican since Herbert Hoover (R-IA) in 1932, with Democrats winning the city by single-digits in just one election since then. The Philadelphia machine has been vibrant for a long time, but it has swung a collective eight points to the right in the last three elections. Trump improved upon his 2020 vote in Philadelphia proper by two points, taking 19.94% to Harris’ 78.57%.

However, the “collar counties” of the city tell the bigger story.

Bucks County is the fourth-most populous county in the commonwealth. It’s a heavily-white county that is currently seeing a biotechnology boom, with the Greater Philadelphia Area consistently ranking as one of the best geographic regions for the industry.

Although Philadelphia has long been a Democratic bastion, its collar counties were much more Republican leaning. Bucks was no exception, having backed Republicans in all but seven elections from 1880 to 1988. However, in 1992, it began its Democratic voting streak, peaking at an eight-point win for Barack Obama (D-IL) in 2008. Although it found its way back to the center, Joe Biden (D-DE) improved upon Clinton’s margin from 2016.

Despite this, Trump is the first Republican since 1988 to win Bucks County, carrying it by a margin of just 291 votes out of almost 400,000 ballots cast. Although it’s a razor-thin margin, it’s results like these that win statewide campaigns, as a message that can resonate well here, in a well-educated, populous, suburban area, is likely adequate enough to win the state. His narrow win is the thinnest margin for a Republican in the history of the county with no major third-party contenders.

Of the Philadelphia region, Philadelphia County experienced the sharpest swing to the right, clocking in at 4.7% more Republican than last election. Bucks County comes in at 4.4% more Republican, followed by deeply-Democratic Montgomery County at 3.5%, equally-blue Delaware County at 3.1%, and Chester County at 2.7%.

Northeastern Pennsylvania

No other part of Pennsylvania is as well-acquainted with coal mining as the northeastern corner. Scranton is a working-class city that was built up by anthracite coal and iron. Pennsylvania is still one of the leading coal producers in the U.S., thanks mostly to Lackawanna (Scranton) and Luzerne (Wilkes-Barre) counties.

Lackawanna County is a solidly-Democratic constituency, having only backed three Republicans since 1928, all of whom won national landslides. Obama received almost 63% of the vote here in 2012, only for Clinton to take just under 50% to Trump’s 46%. Native-son Biden pulled the margin back, but still within single-digits. Trump’s 48.62% of the vote is the best showing for a Republican here since Benjamin Harrison (R-IN) in 1892.

Meanwhile, just to the southwest is Luzerne County, home to Wilkes-Barre. At its peak in 1930, Luzerne was home to almost 500,000 people and a vibrant factory and coal mining region. However, like many areas within the Rust Belt, downtrending industries led to urban decay and population loss. While coal mining and manufacturing are still parts of the local economy, much of the base is now supplied by warehousing.

Luzerne County was once prime swing territory and a bellwether within Pennsylvania; it backed the winner of Pennsylvania in every election from 1936 until 2020. As Pennsylvania grew more Democratic from 1992 onward, so did Luzerne. However, the working-class population here shifted in 2016, going from a county Obama had won by five points to one Trump had won by nineteen. The shift remained clear, and not a fluke, as Biden only improved the margins modestly. Luzerne backed Trump by nineteen points in 2024.

Luzerne County is one of the best examples of working-class abandonment of the Democratic Party across Pennsylvania, as well as an excellent case study in the inside-out decay of the Rust Belt towards the end of the Twentieth Century. Many other Pennsylvania counties have experienced similar tectonic shifts from the Party of Jackson to the Party of Lincoln, but Wilkes-Barre is a major population center for Democrats to lose in such a politically influential state.

Nearby, Trump also flipped back swingy Northampton County and delivered the closest result for a Republican since 2004 in Lehigh County, home to Allentown and a 26%-Hispanic population.

Monroe County, home to Stroudsburg, borders Lackawanna County. Monroe experienced the greatest rightward shift in the commonwealth this year – 7.1% – and it backed a Republican nominee for the first time since 2004.

Harrisburg and Central Pennsylvania

Central Pennsylvania is where the ground shifted the least, with Trump making only modest gains in rural, intensely Republican counties where his ceiling was essentially already met in 2020. Harris, on the other hand, actually overperformed Biden in ten central counties, but only one county (Cumberland) backed her by more than one percentage point. In short, these were very marginal shifts in a part of the commonwealth that once wielded more power.

In Dauphin County, home to capital Harrisburg, Harris won by about six points, down from Biden’s nine-point win four years ago. The county has not backed a Republican since George W. Bush (R-TX) in 2004. Prior to that, Dauphin was an intensely Republican county, only backing two Democrats between 1880 and 2004.

Centre County (State College) backed Harris by a narrow three-point margin, smaller than Biden’s five-point win, but better than Clinton’s two-point win. The swing county doesn’t hold as many votes as Lackawanna or Luzerne, but in a premier swing state like Pennsylvania, it can make a difference at almost any juncture. Centre had been a Republican county until 2008. It shifted 1.9% to the right this election.

Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania was once the base of Democratic support, namely working-class steel town support. Like the coal ranges of northeastern Pennsylvania, the western part of the state also experienced its own decline, leaving decrepit small towns across the landscape.

The working-class shift is readily apparent in western Pennsylvania, with nearly all western counties having backed Bill Clinton (D-AR) and Al Gore (D-TN), only to see just Allegheny county (Pittsburgh proper) stick with the Democrats today. Having last backed a Republican since 1972, Allegheny registered as less than 0.1% more Republican this election compared to 2020.

In neighboring Westmoreland County, Pittsburgh’s working-class shift is more evident. Westmoreland backed Republicans from 1888 until 1928, going for Democrats in all but one election from 1932 to 1996. The county has been Republican since 2000, but Trump’s 63.65% is the greatest margin for a Republican in history.

Finally, in Erie County, in the very northwestern corner of the state, Trump flipped the county back after having flipped it in 2016. Considered a must-win bellwether county of the commonwealth, Erie has sided with the Pennsylvania winner since 1992, peaking at a twenty-point margin for Obama in 2008.

Trump flipped and won the county by over one percentage point in 2016, down from Obama’s massive seventeen-point win in 2012. Biden flipped Erie back narrowly, but Trump won it by an even closer margin than in 2016. Erie is all but certain to remain a crucial swing county going forward.

All surrounding western counties shifted towards the right, ranging from less than 0.1% to 4%. Only three western counties swung towards Harris, all by less than 1%.

A Note on the Senate Race

Dave McCormick’s (R) win in Pennsylvania is perhaps one of the greatest upsets this century, so far. Bob Casey, Jr. (D) was a vetted, three-term incumbent who had three decisive wins under his belt and name recognition owed solely to his father, a beloved governor of the commonwealth. Entering the 2024 Senate elections, Casey looked to be the most well-suited of the three Rust Belt Democrats.

Nevertheless, the staple that he is, Casey lost to McCormick in the closest U.S. Senate race in the commonwealth’s history. The race took three weeks to be called, with Casey formally conceding that day. A recount confirmed the result of the election.

Despite Trump taking the state, McCormick lost three counties that Trump had won: Erie, Monroe, and Bucks.

This marks the first time since 1880 that Democrats lost Pennsylvania’s electoral votes as well as an incumbent Senator in the same election.

Notably, McCormick’s 0.25% margin is thinner than that of the percentages of votes earned by three other third-party candidates.