Last weekend played host to the Town of Islip’s Civil War weekend, full of battle reenactments, live workshops with members of the Town History department, and education on life during the bloodiest war in American history, all set on the historic property of the Islip Grange in Sayville.

The Town of Islip has a unique relationship with the Civil War and even had a battle fought within the town’s lines. Small northern towns were called upon to volunteer troops for the battle, and Islip was no exception. The Town of Islip passed its first wartime resolution on August 19, 1862, which called for an initial sum of $20,000 to pay salaries to the Town’s volunteers in $100 in annual wages for a period of three years of service.

Islip’s next board resolution came in April 1863, which promised full financial benefits to the families of those recently killed for the duration of the war, or until a government pension could be offered. This came off the heels of the Union Army’s losing streak to General Robert E. Lee and the Confederacy.

Seeing the staggering casualties – 144,000 by 1683 – the Town of Islip chose to pay bounties to Suffolk County in place of drafting residents. Additionally, the Town raised local soldiers’ annual wages as an incentive to fight in the war. The first Town Board meeting of 1864 called for $6000 to be raised to pay such bounties to the number of volunteers to satisfy President Lincoln’s (R-IL) call.

Islip had the largest recordable enrollment in the Civil War of any of Suffolk’s townships, at 23% of the eligible male population. Families from Oakdale, Islip, Bayport, Bay Shore, Central Islip, Ronkonkoma, and Hauppauge fought in the war. Since some hamlets were not yet organized or recognized, it has been determined that some soldiers from Islip hamlet resided in East Islip, Islip Terrace, or Great River.

Some misconceptions state that no battles were physically fought in or near the Town of Islip, but the August 1864 battle erupted in the waters off of Fire Island. The CSS Tallahassee brought the fire to the waters of the Town, sparking the phrase that would be repeated during the Cold War: “Where is our Navy?”

The Tallahassee, although not ideal for ocean commerce raiding, proved lethal under the right command. It sank thirty ships off the North Atlantic coast in less than two weeks in August 1864, most of which were sunk within sight of Fire Island. The crews affected by the formidable ship were often taken aback by its sudden presence, as its stealth and speed earned it notoriety during the war.

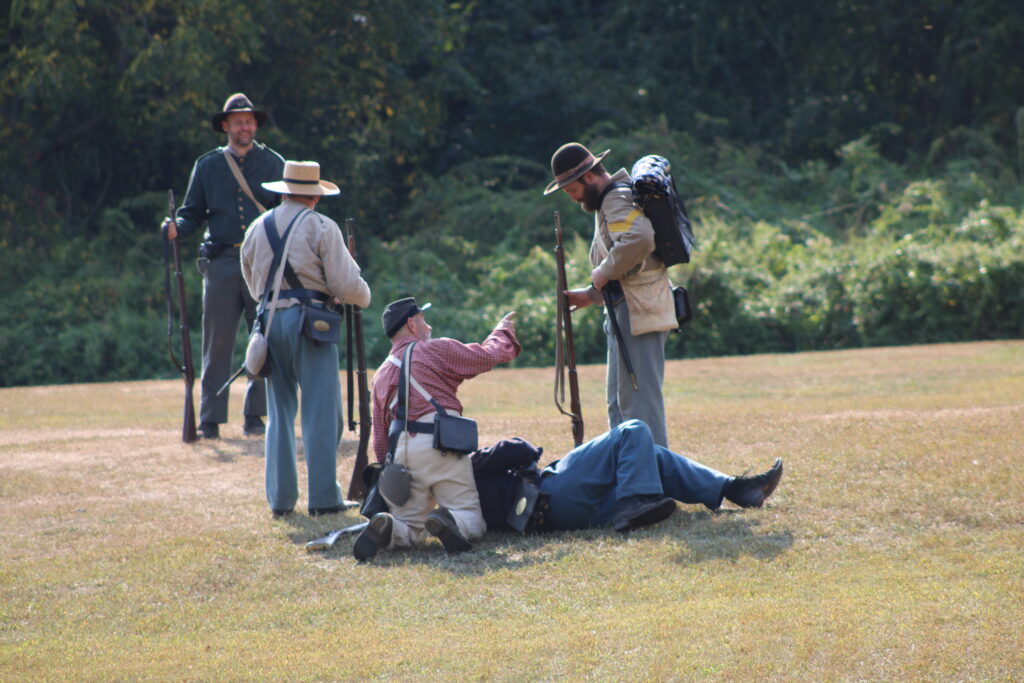

The Civil War day also featured battle reenactments, complete with cannons and period-appropriate firearms. Town Historian George Munkenbeck also narrated most of the battle, explaining to the audience the tactics and battle etiquette used during the time.

Munkenbeck then assumed the role of a doctor at a Civil War field hospital. While educating attendees on common wartime remedies, he was interrupted by a wounded soldier brought in from the previous battle. Munkenbeck demonstrated to the audience how Civil War physicians would tend to their patients, noting that alcohol was seen as a stimulant, when it is now known as a depressant, and that germ theory had not yet been developed. Only shortly after the war would the threat of sepsis be understood.

Munkenbeck said that soldiers could live after sustaining injuries during battle, but if injuries were so severe, he said that a patient would be given a large dose of alcohol, told to sit under a tree, and “wait for the end.”

The wounded soldier had convincing makeup that showed just what kind of battle scars were obtained by Civil War soldiers of either army.

“My grandfather’s uncle fought in the Civil War. His family wanted to go back to England, but he refused to leave. When he turned eighteen, he volunteered for the Fourteenth Brooklyn,” Munkenbeck told The Messenger. “He died of typhoid fever, only days after the army discharged him.”

Munkenbeck described the buildings at the Grange, most of which were transferred to the site from around the Town of Islip. The gazebo is in its original form from when it was taken from what is now Byron Lake Park in Oakdale. The small cottage nearby the gazebo was a real estate office in Sayville where Dunkin’ Donuts is today. Most of the land within the Town was sold in that office. The barn is suspected to date to at least 1830, but Munkenbeck assumes it’s older than that. The barn was originally on a Bayport farm from the 1800s. The windmill was part of the Jones Estate and was moved by horse and wagon as a single unit to Bohemia. It remained there until the farm was sold for development and the windmill was given to the Town.

“They had to cut it in half to bring it down here [to the Grange] because nobody could figure out how to get it down here as one piece,” said Munkenbeck, adding that if the windmill is properly connected, it would pump water.

Islip’s Civil War not only connects the community to a pivotal time in U.S. history, but also connects the community to history that took place right in their own backyards.