Each election year, the conversation is typically dominated by the swing states, those that are usually perennially competitive, and the battlegrounds, those that may not be typically contentious but emerge as such in a given election cycle. Most pundits and outlets use these terms interchangeably, but we tend to classify them as separate ideas and to better highlight the unique electoral prospects afforded to either party each cycle.

But there is another element to a state’s electoral profile that can greatly influence its competitive nature: elasticity.

In short, elastic states are those that can swing wildly between two or more cycles. This doesn’t necessarily earn it the coveted title of “swing state,” but it essentially means there’s more ground that can be moved as opposed to the ground in an inelastic state.

Swing States and Battlegrounds

We’ll start by defining what states are most commonly agreed to be swing states and we’ll break down what the qualifiers are for the designation.

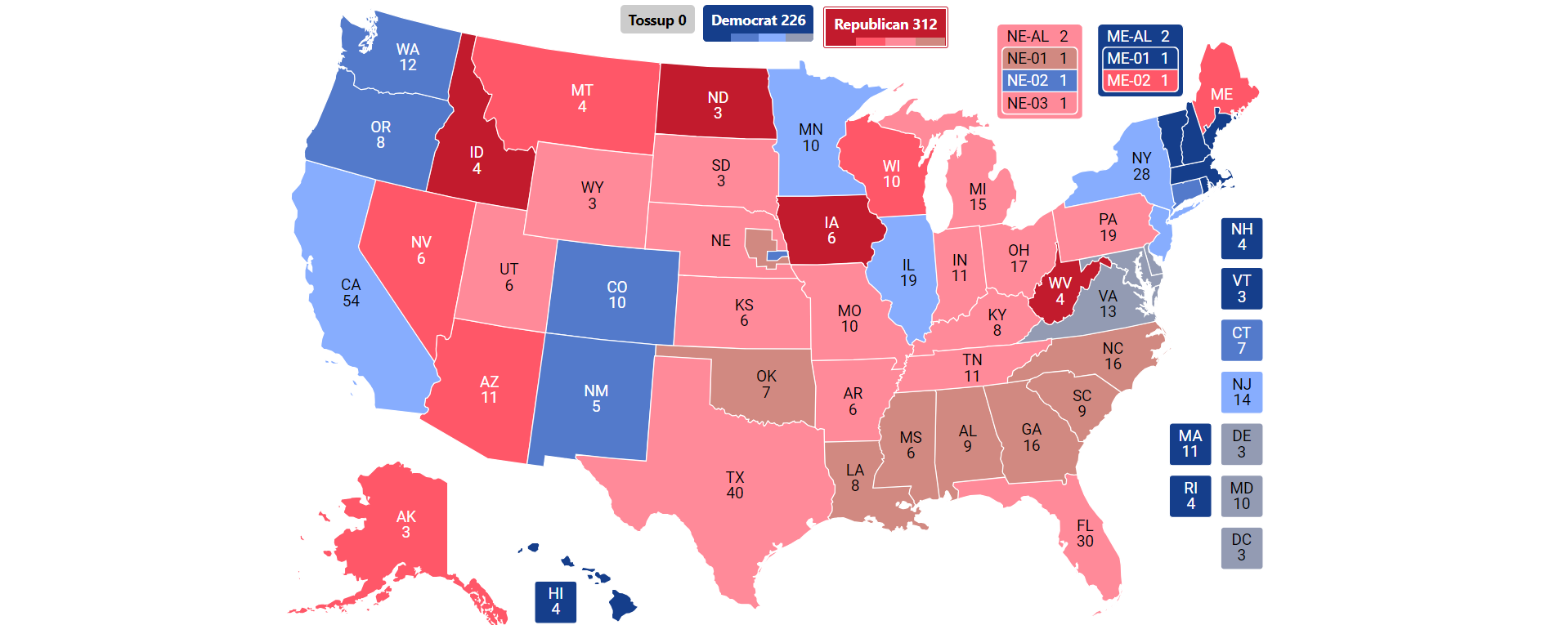

Loosely defined, a swing state is one that either party has a reasonable chance to win in a statewide election, typically carried over a period of time. The top swing states of the century, so far, include Nevada (6 electoral votes), New Hampshire (4), Pennsylvania (19), Ohio (17), Florida (30), and Iowa (6). Going back to 2000, these states were either hotly-contested and/or posted razor-thin results. Wisconsin (10), Michigan (15), North Carolina (16), Nebraska’s Second Congressional District (1), and Arizona (11) have emerged as relatively new swing states, as Republicans have carried Arizona in every election since 2000, except for 2020, and North Carolina in every election since 1980, except for 2008. Wisconsin, although competitive in the early 2000s, never made the shift until 2016, after having back every Democratic candidate since 1988. Michigan was in the same category, having backed every Democrat since 1992 and delivering large margins for Barack Obama (D-IL) in his two elections.

Florida, Iowa, and Ohio have been perennially-competitive states for decades, but appear to be moving off the map, as the new Republican guard consists of working-class whites, blue-collar, union households, and a strong Latino population. There’s a chance these states could become regularly competitive, or play host to one or two tight elections at the presidential level, but overall seem more or less out of reach for Democrats.

The same can be said for New Mexico (5), Virginia (13), Colorado (10), and Oregon (8), all states that were tightly-decided at the beginning of the century, but now have a clear preference of the two major parties. New Mexico and Virginia have shown indications of a renaissance, while Colorado and Oregon have moved markedly off the center of the competitive table.

Swing states are typically defined by demographics, predominantly as it relates to an urban-rural divide and the salience of economic issues over more obdurate stances on policy. In other words, a state’s populace that doesn’t feel overwhelmingly moved by hot-button issues is likely to be more regularly competitive.

Some of the aforementioned states fit into the battleground category. While these states might not pose realistic chances for either party each year, the thin margins and high floors of support a party might have in these states can help dictate the race. For Democratic-leaning states, battlegrounds include New Mexico, Virginia, Minnesota (10), and Maine (4 split). For Republican-leaning states, Texas (40) and Georgia (16) are states where Republicans might be able to rely on a decent level of support, but the races warrant watching.

Battlegrounds might be stubborn in their roots for one party, or they might be shifting into safer territory after a few cycles of contention. These states might take certain policies more seriously than others and demographic voting blocs likely ensure one party continually has the upper hand.

Having explored the differences and similarities between these states likely to decide each presidential election, we’ll discuss the element that can make a state truly competitive.

Elasticity

Pioneered by FiveThirtyEight, elasticity measures how responsive states, and even congressional districts, are to the changes at the national level. Elasticity scores intend to show, by a point-for-point value, how much support one party could expect to gain based on their performance nationwide. An elastic state can be, although not necessarily so, prone to large shifts relative to the environment at large, while inelastic states are not likely to be moved much by national political winds.

The methodology for the elasticity scores are derived from a state’s demographic makeup: race, religion, and partisan identity are the big categories of concern. Unsurprisingly, elastic states tend to have more of a middle to court. These voters might be apathetic to certain hot-button issues, exclusively concerned on economy and national safety, or they might be voters who weigh their options carefully between the two parties. In swing states or battlegrounds that happen to be highly elastic, these voters often decide the elections overall.

The important aspect to note is that elasticity does not necessarily entail competition, nor is it guaranteed that a state will mirror national results, no matter how much the environment swings between cycles. It’s just a metric to understand how volatile a state’s results could be in theory.

The elasticity metric is often used by campaign strategists to gauge their audiences and employ certain talking points, negatives versus positives, and invest in get-out-the-vote initiatives aimed at certain voters.

Elasticity scores are represented by decimal figures, with an integer of one being the control representative of the national environment. When a state’s score exceeds or is less than one, the remainder is indicative of that state’s expected swing relative to the environment.

For example, a state with an elasticity score of one means that the state is not expected to move very much based on the environment. As of 2020, Indiana and Kentucky, both solidly-Republican states, have elasticity scores of 1.00. This means that neither state is expected to move much from their typical partisan lean in the event of a national swing.

According to FiveThirtyEight’s study, the most elastic state, based on 2020 results, is New Hampshire, with an elasticity score of 1.28. This means that for every one percentage point the national political mood shifts towards a party, New Hampshire is expected to move 1.28 percentage points in that same direction. In short, the elasticity score finds that New Hampshire is likely to vote farther left or right of the national environment, depending on the winner.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton (D-NY) won the national popular vote by 2.1% and she carried New Hampshire by just 0.37%. In 2020, Joe Biden (D-DE) won the popular vote by 4.5% and New Hampshire by 7.35%. The elasticity metric shows just how much more the state will swing relative to the environment, and New Hampshire’s voting patterns are similar in previous elections.

With New Hampshire as the most elastic state, Rhode Island follows at 1.26, Vermont at 1.23, Maine and Massachusetts tied at 1.17, and Hawaii at 1.15. Iowa comes in close at 1.13

Save for New Hampshire and Iowa, also the two earliest primaries on the calendar, the remaining states are solidly Democratic. Maine is considered a blue-leaning battleground that was surprisingly close in 2016 after being conspicuously absent from the campaign trail in 2008 and 2012. While pre-election polling might not have detected a swing in Maine, the elasticity meter likely did.

What makes these states elastic is a large middle ground, fiscal conservatives, social liberals, and perennially high turnout. These states often give third-party candidates large percentages of their votes. Republican states with high elasticity scores consist of Alaska, Idaho, and North Dakota, all states that do not fit into the evangelical fold of the GOP, and ones that flirt with third-parties much more.

Also of importance: Only three of these states are considered competitive at the presidential level. The others are overwhelmingly not. These are prime examples of how elasticity does not always predicate competitiveness.

Inelastic States

If a large “center” of the voting bloc and a politically-active base are indications of elastic states, then inelastic states are formed from mostly the opposite, although not always. Inelastic states are primarily those with much less middle to court, making campaign strategies turn to a game of reliable party base turnout over talking points that try to sway voters on certain issues.

These states might be more lock-solid in their beliefs on hot-button issues, or they might be more ancestrally faithful to one political party. Tonal changes from the elephants and the donkeys over the years can also contribute to a state’s middle ground falling off and one party being clearly preferred over another.

As of 2020, the state with the lowest elasticity score is Mississippi at just 0.79. This means that for every one percentage point the nation swings, Mississippi will likely lag behind at around three-quarters of the rate. Mississippi is followed by Alabama at 0.81, Georgia at 0.84, Maryland at 0.87, and South Carolina at 0.88. Virginia isn’t far behind at 0.92 and North Carolina at 0.94.

Although not a state, the District of Columbia has the lowest elasticity score: 0.62.

For such inelastic states, we have an array of competition. Mississippi and Alabama are staunchly Republican, while South Carolina religiously backs the GOP, but by thinner margins than its Bible Belt neighbors. Maryland is one of the bluest states in the nation, while Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia all rest at varying levels of contention.

As stated before, ground game in these states comes to a party getting as many of its core voters to the polls on Election Day. The middle, while still existent in these states, does not stand to impose the same impact on the state’s results relative to how much they might swing nationwide.

As Independents can often decide elections, especially in the crucial suburbs, making inroads in inelastic states might be tougher than in one with significant nonpartisans.

New York, NY-01, and NY-02

New York’s elasticity score sits at 0.96, meaning that when the nation shifts one point in either direction, New York isn’t too far behind.

NY-01, encompassing the East End, Smithtown, most of Huntington, and northern and eastern Brookhaven, has a 2018 elasticity score of 1.02, meaning the independent voter might carry the district slightly beyond the national swing.

NY-02, including southern Brookhaven, Islip, Babylon, and parts of Oyster Bay, has a 2018 elasticity score of 1.01.

Again, elasticity does not necessarily mean competition, nor does inelasticity mean one party can easily rely on decent margins. It’s simply another way of looking at how just how idiosyncratic and unique our country is down to the local level.