An important aspect of understanding civics is understanding that governor’s races, or gubernatorial elections, are often of a completely different strain of electoral participation, and can very easily not reflect the typical partisan lean of a state.

What Makes a Gubernatorial Race Different?

Gubernatorial races are almost entirely dependent on candidate quality. This isn’t to say that candidates with poor likeability or jaw-dropping gaffes haven’t cost themselves races in other means, but what it does mean is that people will respond more idiosyncratically when local issues are discussed on a large platform.

Partisan politics and soundbites to attract certain blocs of voters often suck all the oxygen off a debate stage, especially in today’s hyper-partisan environment. U.S. Senate races were often much more of a mixed bag, with ancestral political DNA often deciding factors in high-profile races that usually decided balance of power in Washington. Since each state gets two U.S. Senators each, there was also often more of a proclivity among voters to keep control divided. “Split” Senate delegations refer to states with one Senator of each party. Just ten to fifteen years ago, blue states like Rhode Island and Oregon had Republican Senators, while red states like South Dakota and Nebraska had Democratic Senators.

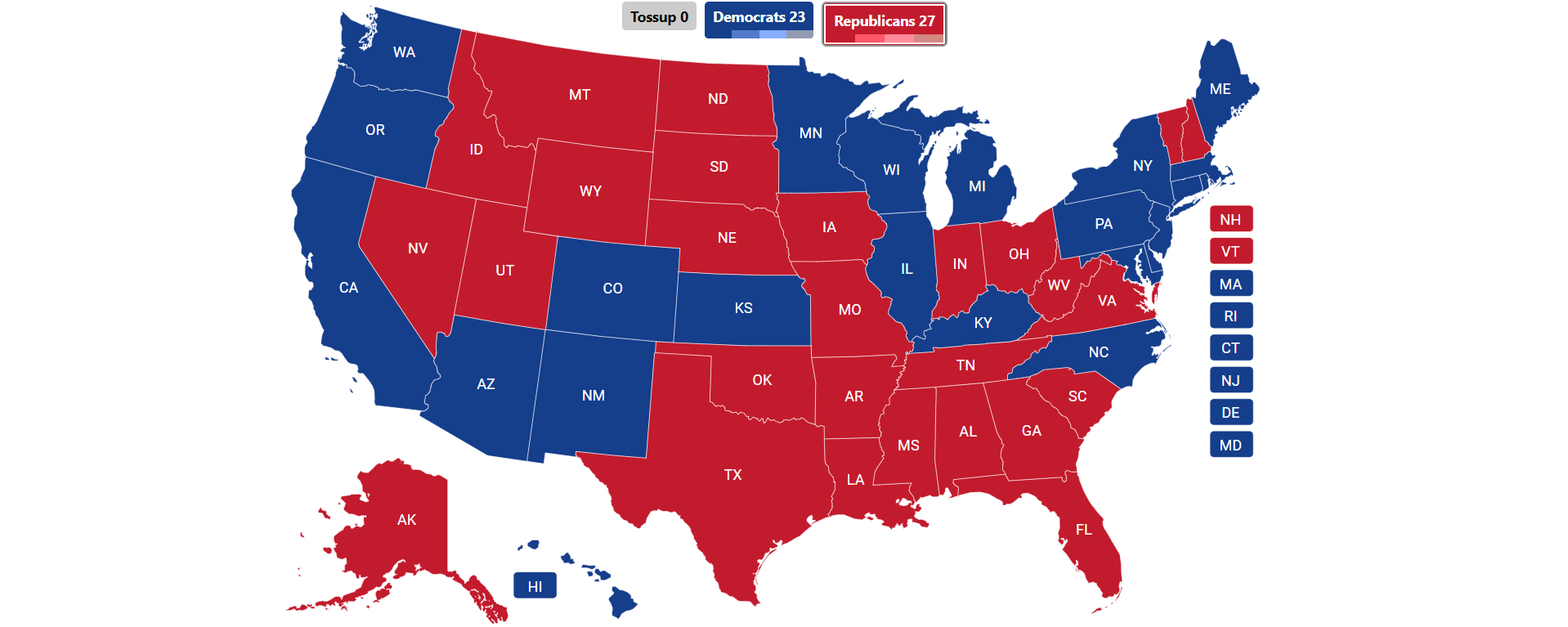

Today, this is not the case. As partisan tensions have risen exponentially, voters are less inclined to split their tickets, which has resulted in just five states with split Senate delegations: Maine, Montana, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Vermont and Arizona technically have Independent Senators, but they both caucus with the Democratic Party. The five split delegations is the lowest number on record since the U.S. began directly electing Senators in 1914.

The U.S. House is more prone to split-ticket voting, as representatives can make their cases to much smaller segments of the population. Districts that are won by a certain party at the presidential level but by another on the House level are called “crossover” districts. Some include NY-04, represented by Anthony D’Esposito (R-Island Park), as Joe Biden (D-DE) carried the district by almost fifteen points in 2020. Another is PA-08, represented by Matt Cartwright (D), while Donald Trump (R-FL) won the district by four points in 2020.

Crossover districts have dwindled as well, but still reflect more intimate connections with the district than other elections.

Unlike the other two forms of representation, gubernatorial races have much greater tendencies of casting aside federal politics and typical partisan lean. Where this materializes is with intimate connections and discussions on the local issues. Additionally, as governors are more often than not lighting rods for every problem in their states, it becomes a much taller task to advertise themselves to voters if their approval ratings slip.

Gubernatorial competition doesn’t necessarily translate to other forms of contention, again, mainly owing to today’s hyper-partisan politics. A tight governor’s race doesn’t necessarily predicate a tight presidential race, nor does it necessarily mean a state is becoming competitive simply because of a race.

The Current “Mirage”

One could argue that certain states with governors of different parties than one would expect could be indicative of more down ballot success, but typically, it’s more or less a referendum on good policy by an underdog or bad policy by a favorite son. In some cases, it’s more or less a “mirage.”

While Vermont is one of the bluest states at each level, the state has been governed since 2016 by wildly popular liberal Republican Phil Scott. While Virginia and Nevada are blue-leaning battlegrounds, they’re run by Republicans. The same was true for Maryland and Massachusetts until 2023, Illinois, New Mexico, and Maine until 2019, and New Jersey until 2017.

On the other side, Democrats currently enjoy control of Kentucky and Kansas, as well as the red-leaning battleground of North Carolina. Democrats also governed Louisiana until 2023, Montana until 2021, and Missouri until 2017.

Good Governance on Display

Even the bluest and reddest states aren’t immune to governors of either party shaking things up, and one election cycle in particular proves it: 2006.

In 2006, Hawaii, one of the most Democratic states, re-elected Governor Linda Lingle (R) with a landslide 62.5% of the vote. She carried every county. She is the first and only Republican governor of Hawaii who earned re-election. To date, it’s the last time a member of the GOP won any statewide race here.

In the same exact election cycle, Wyoming, the reddest state, re-elected Dave Freudenthal (D) with a landslide 70% of the vote. He carried every county. It’s the last time a Democrat carried every county in Wyoming and won any statewide election in the state.

In just one election night, the bluest and reddest states re-elected governors of opposite parties by landslide margins. This is the result of good governance and keeping constituents content. By today’s metrics, these might be tougher pulls on paper, but they’re still not impossible by any stretch of the imagination.

This also allows for a much higher concentration of Independent or alternative party candidates winning gubernatorial elections. Jesse Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota under the Reform Party label in 1998. In 2014, Independent Bill Walker was elected governor of Alaska, the state with the highest rate of third-party voters.

Patterns are Important

Something to note with gubernatorial elections is how important pattern analysis is. Just because a state leans one way or the other, or had a fantastic governor of an opposite party does not necessarily mean the same party is a shoe-in next time around. It depends mostly on term limits.

Many states subscribe to the two-one-two-off pattern of electing governors, in which they will elect a governor of one party for two terms, and then switch back to the other party for two terms. Two states that have embodied this unofficial rule consistently are Michigan and Kansas. Some say Laura Kelly’s (D) victory in the Kansas governor’s race in 2018 was an upset. However, the state had elected two terms of Sam Brownback (R), who earned notoriety as one of the nation’s most unpopular governors, and before him, two terms of Kathleen Sebelius (D), who later became Obama’s HHS Secretary.

Term Limits

Each state handles term limits differently. Nine states have lifetime limits of governors who have served two four-year terms. Eleven states, including New York, feature no term limits with four-year terms. New Hampshire and Vermont have no term limits, but are the only states to feature two-year terms.

Twenty-three states limit governors to two four-year terms, reeligible after four years.

Other states have different rules. Virginia is the only state that limits governors to one term but are reeligble after four years. This was on display in 2021, as former Governor Tery McAuliffe (D) served as governor from 2014 to 2018 and ran again in 2021, losing to Glenn Youngkin (R).

For another odd example, Indiana and Oregon limit governors to two four-year terms, but they’re eligible in eight out of any twelve years to serve.

When Enough is Enough

Sometimes, a gubernatorial race can have a massive reshaping effect on state politics. Some say that Lee Zeldin’s (R-Shirley) near-upset of Governor Kathy Hochul (D) in 2022 has begun a tectonic shift of one the nation’s most Democratic states back towards the center. While it may still be too early to tell, polling shows that the GOP might be able to put New York somewhere on the map this year.

2024 Outlook

Eleven states will elect governors in 2024. Most do not seem very competitive. The Messenger rates North Carolina and New Hampshire as Toss Ups, with Missouri as Likely Republican and Washington as Likely Democratic.