“You can’t just love something– you also have to take care of it.”

A self-portrait is to a painter as an autobiopic – that is, an autobiographical epic – is to who else, but one of the greatest living filmmakers? With Steven Spielberg’s natural born gift for cinematic storytelling, though, came a double-edged sword. His enhanced perception skills led him to discover a family secret that once broke his spirit as much as it’s come to lift it since.

“Every one of my movies is a personal movie,” Steven Spielberg told CBS News. “I don’t make films that I don’t consider to have something of myself left behind in them.”

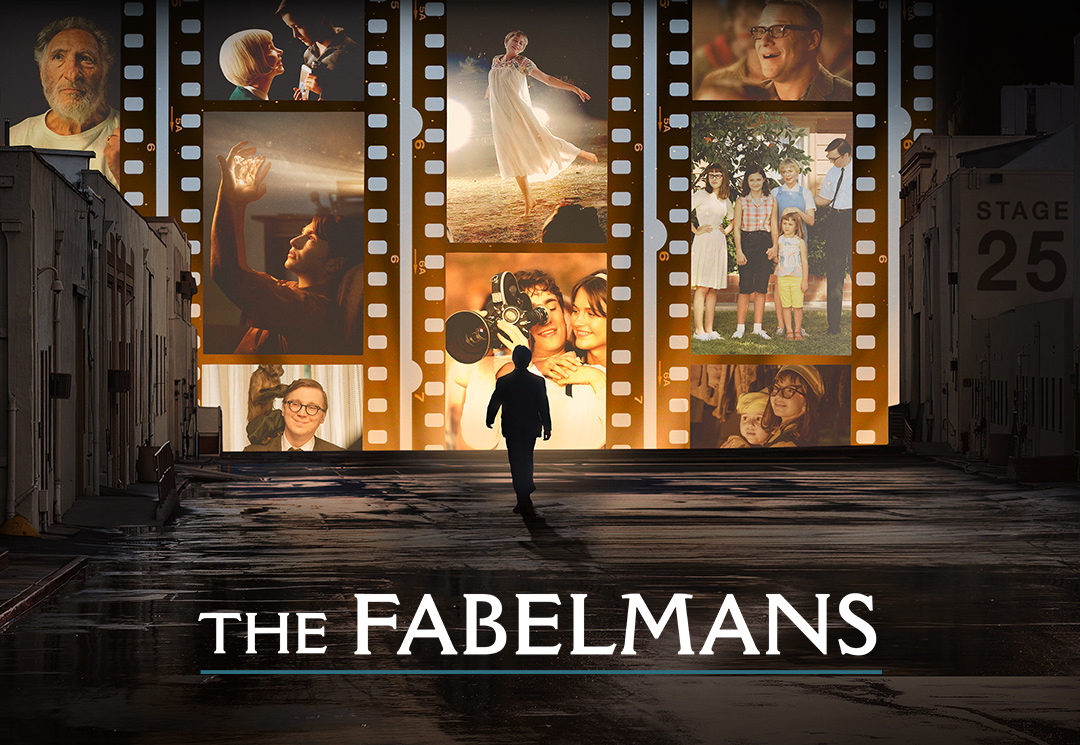

The Oscar-winning director of Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan’s (1998) latest – a names-changed, but otherwise authentic means to make his boyhood come alive – released theatrically in time for the whole family to enjoy from Thanksgiving on through to Chanukah and Christmastime. Even those not keen on viewing films in terms of directors’ body of work will get a kick out of The Fabelmans’ final scene. There’s next-level demonstrations of wink-to-the-camera commentary, and then there’s that.

Those familiar with Spielberg’s chock full of classics catalog who have seen The Fabelmans – currently in theaters across Long Island staples like Island 16 Cinema de Lux in Holtsville and the mid-renovation AMC Stony Brook Loews in Lake Grove – can attest to each point. Sharing with the world the impact his parents’ marital decay had on him cuts even deeper when one recognizes Spielberg has traversed such narrative terrain prior. E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade (1989) and Catch Me if You Can (2002), to name a few, all very much feature protagonists grappling with a cloud that hangs over them called the absentee father.

The lattermost labor of love cast an early 1960s divorce announcement as the catalyst that sent real-life grifting teenager Frank Abagnale Jr. (Leonardo DiCaprio) running toward what would turn out to be the chase of a lifetime. Conversely, The Fabelmans builds to its Earth-shattering blow for Spielberg-by-another-name, Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle). Sammy’s arc from The Greatest Show on Earth-traumatized boy to clearly-burgeoning blockbuster man is explained by Spielberg’s own well-known penchant for fantasy. Known now more than ever, his foremost desire has long-been to escape into movie screens where families, like his, can be made whole again.

But, even braver, The Fabelmans allowed Spielberg to confront that familiar fracture is OK, and an experience more families resonate with than he ever realized.

Spielberg’s most daring project — one that required equal amounts of sensitive family drama exploration as it did self-introspection — had the posthumous approval of both his parents, immortalized on film by Michelle Williams and Paul Dano.

“Well, it was cathartic for me, certainly. I never took it for granted,” said Spielberg. “I mean, it’s a tremendous privilege to — it’s like making a movie, you know, and realizing with this movie, what have I just done? Has this been $40 million of therapy?”

Munich (2005) and West Side Story (2021) scribe Tony Kushner happily dictated memory lane-born anecdotes of Spielberg’s before the script found its structure. Kushner’s negging, plus the soul-confronting early days of the COVID pandemic, inspired Spielberg to deem The Fabelmans a priority project.

In deciding to move forward, he joined generations of filmmakers he influenced – Paul Thomas Anderson, Kenneth Branagh, Noah Baumbach, Richard Linklater and Quentin Tarantino, among others – aboard the popular movement wherein seasoned filmmakers tackle their own coming-of-age.

In a true three-acter that takes us from 1950s New Jersey to 1960s Arizona and California, it appears as the Spielberg/Fabelman patriarch’s computer science career blossomed thanks to the IBM wave, Spielberg’s ability to fit in suffered. Even portraying his anti-Semitic class bully heroically got him in hot water, because it made the subject realize how spectacularly asinine of an individual he really was.

Everyone from the dinner table to his boy scout troop to prom knew who he was going to turn out to be, but the guilt Spielberg felt from realizing the truth his camera could capture made him nearly put it down for good.

Almost. For when the same reluctant director of a beach-set “senior skip day” documenter freed himself from trying to control the things he couldn’t control, he’d evolve into someone who demanded his way onto studio lots he’d once merely stumbled onto, and end up making Jaws (1975) by age 30.

And the rest, as they say…