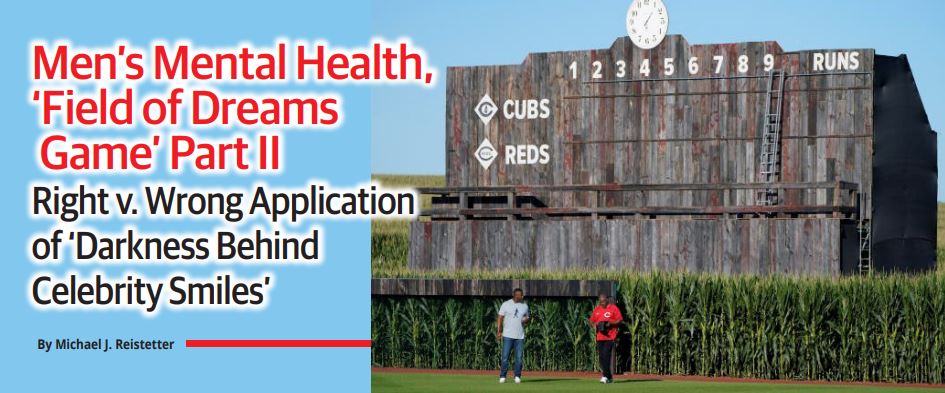

For the second straight year, I skipped the “Field of Dreams Game.”

Last year, it was on the grounds that a relic of my childhood – my all-time favorite film – was commercialized in a way that ran counter to the film’s very message. I didn’t sit down to watch it this go-around either on August 11. But I did catch enough in my feed to appreciate the incorporation of Ken Griffey Jr. and Ken Griffey Sr. staged to emerge from the film’s (replicated) Iowa cornfields.

At the same time, I wonder how many people interpreted this moment as I did. Behind the famous, ear-to-ear grin of one of the greatest to ever do it and his All-Star father, exists a darker story: one about the greatest that very nearly never was.

“It seemed like everyone was yelling at me in baseball, then I came home, and everyone was yelling at me there,” the 1997 American League MVP told the Seattle Times in 1992. “I got depressed. I got angry. I didn’t want to live.” Hailed an athletic prodigy from an early age, Griffey Jr. attempted suicide at 17-years-old in by swallowing 277 aspirin pills, citing pressure from his father and his coaches. Moreover, it was not the first time he contemplated ending it all.

However, it was the first, and only time, he attempted. A hospital stay, a first-round overall draft pick selection and a quick ascension through the minor leagues later, and the future Hall of Famer was hitting back-to-back homers with his father as a second-season Seattle Mariner in 1990.

Despite the Seattle Times interview, this story of backdoor torment and the psychological burden of expectations did not gain much momentum until mental health as applied to high-profile entertainers was no longer considered taboo. In the era of platforms like The Players’ Tribune, founded by Derek Jeter in 2014, athletic stars can now flip the script and tell their truth by cutting out the middlemen journalists tasked to tell it for them.

For every curiously under-shared instance where there is concrete pain behind the most famous smiles, there are countless examples of social media-propagandized notions that all comedians are depressed, too. In fact, no one’s face is attached to this sentiment more than Robin Williams, who died by suicide 8 years ago – also on August 11.

“There’s an idea that I hear a lot, where people like to theorize that comedy all comes from a place of pain and sadness. And people like to talk about comedians as if we do what we do because of some inner darkness. And this is especially thrown around when discussing Robin Williams,” said comedian John Mulaney in Netflix’s The Hall: Honoring the Greats of Stand-Up while posthumously commemorating Williams.

“Have a little respect for a brilliant artist who was just more talented than you,” he quipped. “That’s what was happening. Making people laugh is incredibly fun. The art form of comedy is a joy to perform. And being a comedian is not a psychiatric condition.”

What was a psychiatric condition: the Lewy Body dementia discovered in Williams’ brain, per an October 2014 autopsy. His wife, Susan Schneider, likened the disease to “the terrorist inside my husband’s brain” while reflecting on what drove the comedian to suicide. Yet initial reports Williams hung himself after receiving a Parkinson’s diagnosis rather than fight the disease carried forward. Also erroneously propagated under false pretenses, was that he was a lifelong depressive who had finally “given up.” At this year’s Field of Dreams game, the MLB and the audience alike benefited off the likeness of a pair of Griffey’s side by side – but I didn’t hear anyone talking about the redemptive weight behind this image. Like in the film the festivities annually claim to honor, things couldn’t have been more tense and unresolved between protagonist Ray (Kevin Costner) and John Kinsella – until they were.

Granted, they’re trying to draw in the family numbers. But topics like mental health and suicide are no longer “unmentionables,” so why did they go unmentioned? In an age where the celebration of men’s mental health awareness is confined to just one month, June, it’s the duty of the public to keep spreading the word during all other months. It is also their obligation to assign tales of humanizing woes to the correct public figures whenever applicable.

Regarding Williams, it’s a fruitful reminder: just because you saw something on Facebook, does not necessarily mean it’s true. While it is now public knowledge that he privately fought addiction, Williams did not fight nearly the number of demons the Internet claims he did for the duration of his life. He ultimately would have to face a heap of them in the end, when he was no longer himself per the parameters of his rare condition.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat with 988lifeline.org. For more information on Lewy Body dementia and to donate to the research efforts for a cure, visit www.lbda.org.