The Yankees as we know them got their true start on January 11, 1915, the day the club was purchased by two Colonels named Jacob Ruppert and Till Huston.

The club dates back to 1903 when it was known as the Highlanders. But the Colonels made a real impact

on improving the team, and bringing them into relevance.

One desire they had was to search for a suitable property for their own baseball field. At the time, they were leasing space at the Polo Grounds from the senior club in town, the New York Giants of the National League.

The Colonels were successful in other business ventures, and were not going to accept playing second-fiddle in New York to any other club. They were to be the best.

To be competitive, they had to build a fan base, find a suitable site for their own, build a state-of-the-art baseball plant and generate some economic thrust to turn losses into profits and to finance field construction costs.

Not long after starting the above tasks, the Colonels found themselves thrown onto a tough and frustrating road. Between the summer of 1919 and the spring of 1923, overwhelm plagued the club owners. They would find themselves “blackballed” by most American League owners while contending with endless negative effects from baseball’s “old boys’ network” that constantly worked against them. They were punished repeatedly by Commissioner Ban Johnson, and often had to deal with his questionable player suspensions, fights, and additional lawsuits. Also, they faced sudden rent increases along with persistent threats of losing their lease.

The nonsense continued during construction of the Yankees’ new park located at 161st and River Avenue in the Bronx. There were many suspicions arising from questionable delays in NYC construction approvals, potential labor strikes, delays forcing unnecessary winter issues, recurring cash flow problems and restrictions brought on by the bank and the surety company. At the same time, they were dealing with attempts by others to force the sale of the club due to the effects prohibition was having on Ruppert’s brewery. And it goes without saying: baseball lost many of its fans due to the 1919 World Series “Black Sox” scandal as well.

The Colonels’ war with American League Commissioner Johnson and his five loyalist clubs ran concurrent with the political turmoil of Tammany Hall. Mobster Arnold Rothstein had his hand in everything that moved at that point, and boy, did the Yankees owners sure know it.

They needed an opportunity to gain the upper hand, or risk losing it all. So, they joined forces with Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey and Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee. The teams became known as the American League’s “Insurgent Clubs.” By banding together, they could block votes and prevent actions taken against one or all.

Johnson’s repeated retaliatory actions against the Insurgents made this union necessary. The other five American League clubs remained loyal to Johnson by falling in line as expected. Johnson is credited with founding the new league. Therefore, in his mind, it was his possession, and he would rule as King.

The Colonels, Ruppert and Huston moved ahead and purchased 10 acres in the Bronx directly across the river from the Polo Grounds for their new field. This park was designed to be bigger and better than both Manhattan’s Polo Grounds and Boston’s Fenway Park. The Yankee owners’ foremost problems were coming from Giants owner Charles Stoneham, Giants club manager John McGraw, and Rothstein, New

York’s number-one “Gangster” (and then-part owner of the Giants). In time, the Yankee owners would be hated by Stoneham and McGraw, which was no small thing considering their Tammany connections and the style of play in which they eliminated competition, both on and off the field. Nobody ever dared to

refuse Rothstein. He was smart. He was ruthless. And so were the Giants by association.

Stoneham only made things worse by making an offer that, if successful, would lead to the forced sale of the Yankees franchise while allowing Stoneham and company the blessing of choosing the new owners. This lent them the power to cripple the two Colonels beyond the chance for redemption.

After their alliance formation, the Colonels next required an economic tornado to come down from above with the funds they needed to finance a ballpark grand enough to help them weather the most deafening of storms.

Enter: “The House That Ruth Built.”

Stadium Construction

The Colonels would have to tolerate a slew of construction approval delays from New York City throughout the process. Over 40 companies had bid to serve as general contractors on the Yankee Stadium project. White Construction won the job.

Still reeling from World War I and the Black Sox scandal, the economy and baseball alike were suffering. Fans weren’t as apt to buy a ticket to a game that broke their heart. So when a new ballpark was commissioned in New York, these reasons contributed to the park scaling it back a tad – as it was built in two phases.

“Phase One” would include two decks with a middle level mezzanine, which would run from foul pole to foul pole with seating for an estimated 36,000. In addition, there would be wooden, temporary benches in the outfield bleachers that ran the entire length of the outfield to hold another 21,000 fans. These bleachers would be replaced with more permanent construction under “Phase Two” in 1927. The original plan called for three tiers of seating to completely encircle the playing field.

On April 18, 1922, the Colonels announced that Phase I was expected to be completed in five months. The Yankees originally hoped to play the 1922 World Series in their new park. The Bronx venue was to be called “Yankee Field.” Outside forces, arguments over responsibility and who’s in charge, construction

status, change orders, pricing, cash flow disruptions, deliveries, setting priorities, owner medaling, design changes, scheduling, meeting interpretation delayed this plan until the following year.

Before the project was over, White Construction announced that it was essentially broke. They were out of cash and, unless paid, they were prepared to walk. This would require a major contractual revision to the May 4, 1922 construction contract. Both the bank and the sureties were now asking questions. The Colonels were both having their own cash issues as well. Ruppert’s brewery was trying to survive past Prohibition woes. Huston had already put in all the cash he had to offer. The Yankees’ attorneys would then draw up an amendment and new terms to tackle the crisis head-on.

Not long after these issues were resolved, the bonding company and bank called on White Construction for a full accounting report. Meanwhile, Commissioner Johnson was still scheming in his slippery ways. For example, he altered the opening season schedule to shift financial rewards expected from the Yankee Field’s grand opening to benefit one of his loyalist clubs. He also cried foul at the distance between home plate and the back wall as soon as it was too late to alter construction. Needless to say, he was a constant thorn in their side. Even the planned elevated railway station located at 161st would get delayed. That, in turn, stopped the construction loan in its tracks. The bank stopped their cash advances, causing the trades and suppliers to go unpaid. Rothstein’s far-reaching hand surely played stifling agent once again here.

Legal issues mounted between White Construction, their employees and outside trades and suppliers. The project was getting old, and fast. The Giant owners would take one more stab at the Colonels by requesting conflicting Sunday games played to steal attendance from their cash-strapped neighbors

while in the pursuit of their own new home.

Due to the delays, the Two Colonels would have to go before the Commissioner and petition for consideration from all the owners to postpone the start of the 1923 season to allow for extra time to finish construction. But in the end, it did all work out. But only because all those issues were overcome because of one over-sized baby-faced ballplayer. Baseball history proves that.

He had many nick names such as: “Prince of Pounders,” “Wizard of Whack,” “Wali of Wallop,” “Behemoth of Bust,” “Rajah of Rap,” “Maharajah of Mash,” “Wazir of Wham,” “the Big Bam,” “King of Swing,” “Titan of Terror,” “King of Crash,” “Colossus of Clout,” “Sultan of Swat,” “The Great Bambino,” and simply, “The Babe.” His full name? George Herman Ruth. And he was the force that served as the economic engine most essential to the survival of the New York Yankees Baseball Club.

Babe Ruth not only saved the game of Baseball, he saved the Yankee franchise for Colonel Jacob Ruppert and Colonel Til Huston. He was bigger than them all. The Yankees would go on to play in 29 World Series between 1921 and 1964, and win 21 of them – with the first victory coming in 1923. Famously, that same season, The Babe grandly opened “the house that he built” in the grandest way possible: with a blast to the bleachers.

The first of many.

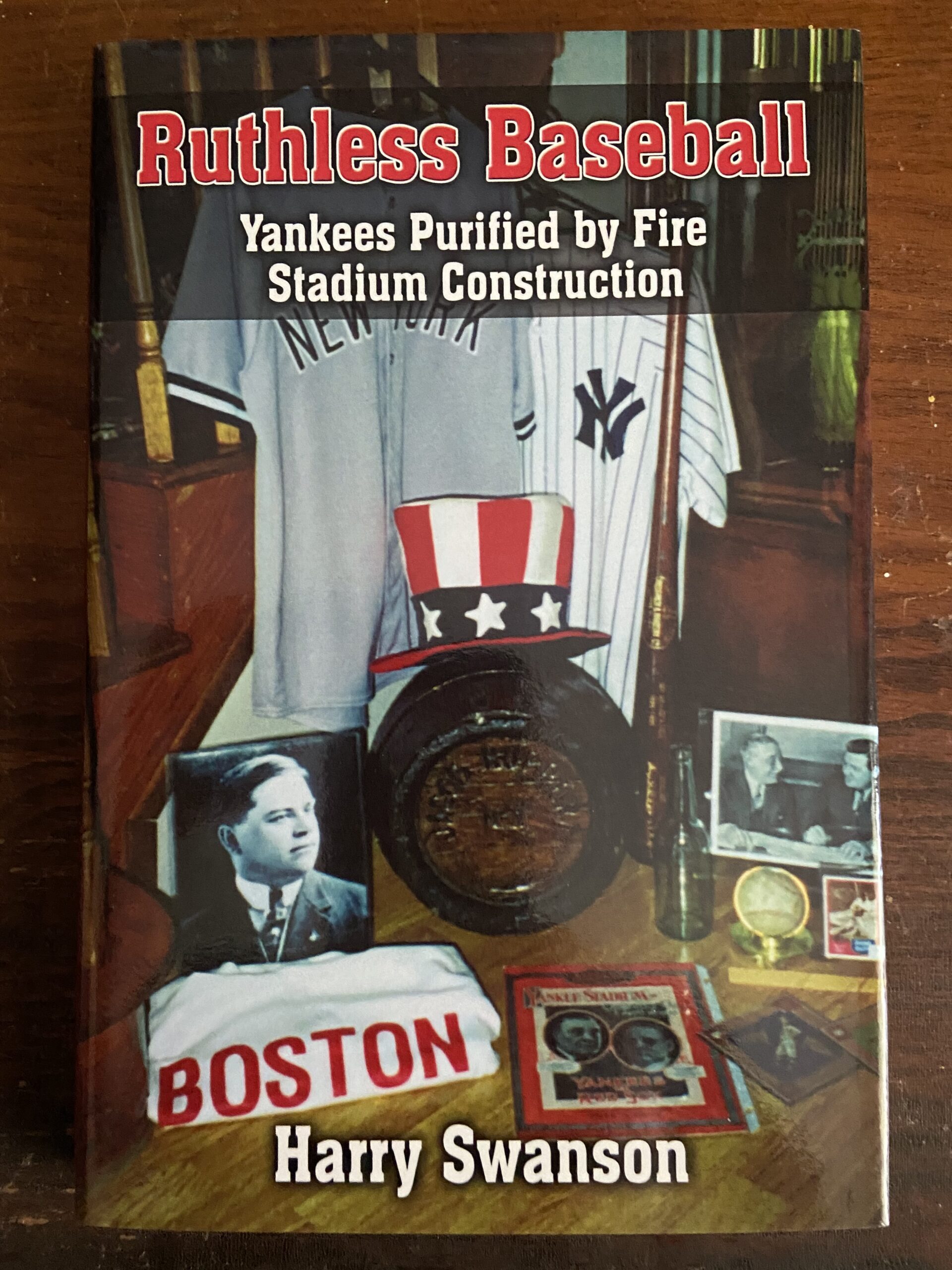

Note: This is a brief summary of Harry’s book, Yankees Purified by Fire Stadium Construction, published by Authorhouse in 2004.