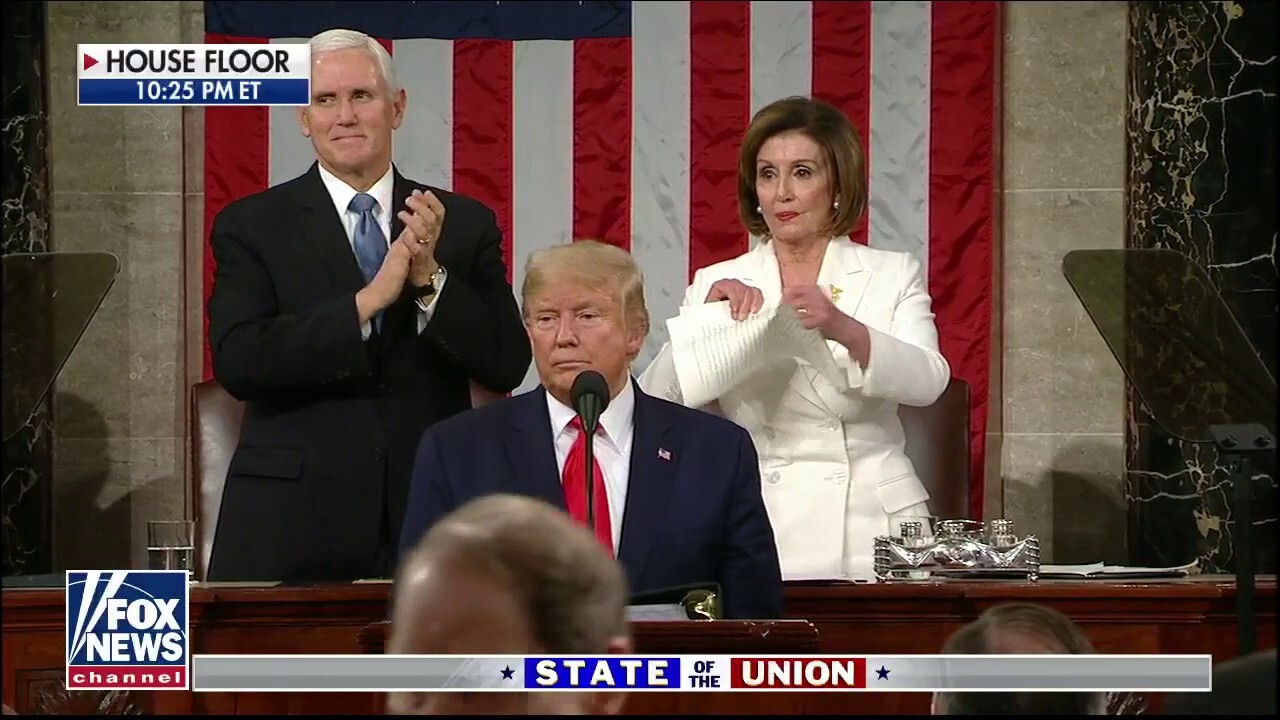

Cover photo: Trump 2020 SOTU, with Pelosi behind tearing up speech.

The State of the Union address, sometimes stylized as SOTU, while required by broad terms by the Constitution, shakes out to be a more traditional display, one that is especially subjective in tone and scope by the president delivering it. We turn to this topic in light of Tuesday night’s State of the Union address, the first of President Donald Trump’s (R-FL) second term and his fifth overall.

History and Origins

Article II, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution states, “He [the president] shall from time to time give to the Congress information of the State of the Union and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

Because of the clause’s vague language, there is no set time of year or particular date on which the address must be given, nor does it stipulate specific policies to be discussed. Similar addresses are given by executives, such as State of the State addresses by governors, and even State of the County addresses by county executives. Suffolk County Executive Ed Romaine (R-Center Moriches) gave his first State of the County address in early May last year.

Regarding presidential State of the Union addresses, George Washington delivered the first regular annual message before a joint session of Congress – a joint session being one where both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate convene together – on January 8, 1790, in New York City. New York was the provisional U.S. capital at the time. Thomas Jefferson would discontinue the practice as he felt it was too monarchical, reminiscent of the Speech from the Throne. From Jefferson, who was elected in 1800, onward, the address was instead written by the president and delivered to Congress to be read by a clerk.

Originally intended to be an update from the president to Congress, the State of the Union address has become more of a line of communication between the president and the American public, especially in the wake of broadcasting, live streaming, and Internet availability.

The practice of a formal address to Congress was not reinstated until 1913, when Woodrow Wilson (D-NJ) resurrected the practice, albeit with some controversy. Nearly every year since, the president has delivered the address to Congress in person. There have been a few exceptions of written statements or broadcasted speeches. The last State of the Union without a spoken address was done by Jimmy Carter (D-GA) in 1981, just days before his presidency ended after his defeat to Ronald Reagan (R-CA) in 1980.

The term to describe the address was “the President’s Annual Message to Congress.” Franklin D. Roosevelt (D-NY) popularized the phrase “State of the Union” in 1934, and that has been the generally accepted term since then.

The State of the Union address was typically held at the end of the calendar year, often in December. However, with ratification of the Twentieth Amendment moved the term dates for both the president and Congress. For the president, the opening of the term was moved from March 4 to January 20. For Congress, the start of terms were moved from March 4 to January 3. This was done to shorten the “lame duck” period for defeated or term-limited incumbents to limit their powers upon exit, as well as to modernize the process, as the U.S. no longer required the months of traveling and transmission to the nation’s capital. Because of this, every State of the Union address since 1934 has been delivered to Congress early in the calendar year, typically in January or February.

It is also customary that the sitting Speaker of the House formally “invites” the president to deliver the address in the House chamber, often prompting a resolution vote to permit the chamber’s space for the occasion.

While newly-elected presidents often give an address to Congress, they’re not typically considered a classic State of the Union address, mostly owing to the new president’s lack of time in office and relative inability to update Congress and the nation on executive intent. While these speeches serve a similar function as the State of the Union address, they’re not officially considered as such.

Warren Harding’s (R-OH) speech in 1922 was the first to be broadcast on radio, and Calvin Coolidge’s (R-MA) 1923 speech was the first to be broadcast across the nation. FDR’s 1936 address was the first to be delivered in the evening, a precedent not followed until the 1960s. Harry Truman’s (D-MO) 1947 address was the first to be broadcast on television. Bill Clinton’s (D-AR) 1997 speech was the first to be broadcast available live on the World Wide Web.

Also bucking precedent, Ronald Reagan’s 1986 speech was the first to have been postponed in the wake of the space shuttle Challenger disaster that morning. In 1999, Bill Clinton became the first president to deliver an in-person State of the Union address while standing trial for impeachment. The speech was delivered on the same day that his defense team made their opening statements in his trial.

In 2019, Trump’s speech that year was originally planned for January 29, but was cancelled after then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D, CA-12) stated she would not proceed with a vote on a resolution to allow Trump to deliver his speech in the House chamber until the end of that year’s federal government shutdown. Her cancellation was a rescission of her earlier invitation to the president, likely the first time in history that a Speaker had disinvited a president from delivering the State of the Union address. The speech was later held on February 5.

The Formal Delivery

Every member of Congress is allowed to invite one guest each to the address, while the president may invite up to twenty-four guests to be seated with the First Lady in a separate box in the gallery. The Speaker may also invite up to twenty-four guests to sit in the Speaker’s box. The Cabinet, Supreme Court Justices, Diplomatic Corps members, and military leaders have reserved seating.

By approximately 8:30p.m. on the night of the address, Congress convenes and is seated, while the Deputy Sergeant at Arms often loudly announces the vice president. The vice president is positioned behind the president’s right shoulder (left shoulder in viewing), while the Speaker is seated to the president’s left. On occasion, if either cannot attend the speech, the next highest-ranking individual occupies the respective seat. The Deputy Sergeant at Arms again loudly introduces, in order, the Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, the Chief Justice of the United States and Associate justices, and the presidential Cabinet.

At around 9:00p.m., the House Sergeant at Arms faces the House Speaker and introduces the president, often followed by a standing ovation, cheering, and handshakes down the center aisle. The president then hands two copies of his speech to the Speaker and vice president.

Customarily, the Speaker formally announces the president before he begins his speech, typically stating, “Members of Congress, I have the high privilege and distinct honor of presenting to you the President of the United States.” However, the Speaker may opt not to do so, as was done in 2019 and 2024.

Traditionally, members of Congress are seated on separate sides of the chamber – literally “across the aisle.” In 2011, Senator Mark Udall (D-CO) proposed a resolution to intersperse the seating in the wake of the shooting on then Congresswoman Gabby Giffords (D-AZ). Sixty legislators signed on, with 160 signing on to a similar proposal in 2012. However, since 2016, the seating arrangement has mostly returned to its partisan makeup.

The Designated Survivor

One Cabinet member does not attend the meeting, called the designated survivor. This is done to protect the line of succession to the presidency in the event a major disaster or concerted attack kills or otherwise disables the president and other members in the line of succession.

Since the September 11, 2001, Attacks, members of Congress have been asked to relocate to undisclosed locations in the event of the same catastrophe. In such an event, the surviving members would form a “rump Congress,” dating back to the term in Seventeenth-Century England. The “rump” normally refers to the hind of an animal, implying “remnants,” and has been used to refer to any members of a legislature left over after the dissolution, formal or otherwise, of the existing at-large legislature. Since 2003, each chamber of Congress has a formally designated survivor.

Speech Contents

The purpose of the speech is merely to update Congress, and the nation, oftentimes rather succinctly. The preamble often goes, “The State of the Union is…,” with many saying “strong,” as popularized by Reagan in his 1983 speech. Gerald Ford (R-MI) had his own spin, by saying, “not good” in his 1975 address.

Apart from discussing statistics and specifics of the nation, as well as policy initiatives sought by the executive throughout the year and his term, special guests are often honored and recognized. Reagan’s 1982 address acknowledged Lenny Skutnik for his heroism after the crash of Air Florida Flight 90, saving the life of Priscilla Tirado after the plane crashed into the frozen Potomac River. Since then, special honorees have been referred to as “Lenny Skutniks.” Other designations can occur in this role, as Trump did in 2020. The unprecedented move saw conservative radio personality Rush Limbaugh awarded the Medal of Freedom mid-speech.

Most of the speech is frequently interrupted by applause, which is often partisan. The party of the president delivering the speech is usually the most jubilant, although some bipartisan moments can be observed in any given speech. Supreme Court Justices often do not applaud in order to maintain the appearance of political impartiality. The vice presidents and House Speakers once adhered to this tradition, but have since broken precedent in that regard.

The Opposition Response

While not mandated by the Constitution, the opposition party of the president has given a response speech since 1966, typically from a broadcast studio with no live audience. The speech is often given by a significant political leader, elected or unelected, of the opposition party. In 1997, Republicans delivered the first opposition response in front of high-school students. In 2004, Governor Bill Richardson (D-NM) delivered the first opposition speech in Spanish. In 2011, Congresswoman Michele Bachmann (R-MN) delivered the response for a political movement, the Tea Party Express. The first Independent response was delivered by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.