A couple issues ago, we reviewed the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution, commonly known as the Bill of Rights. This week, we’re dedicating an entire page to the Twelfth Amendment, one whose text is as lengthy as its history. We haven’t skipped the Eleventh Amendment, we’ll just return to it at a later date.

The Twelfth Amendment sets guidelines for how presidential and vice presidential elections are administered from the end of the federal government, rather than the strict provisions of voting within each state. Our fledgling nation had provisions for formally electing a president, but within just a few years, it would become apparent that the Constitution needed some revisions in the overall process.

History Behind Constitutional Amendments

The two political parties at the birth of our nation, the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists, had different views as to how comprehensive language surrounding government powers should be, primarily because lack of clarity could leave the door open for violations of liberties. Federalists argued that a strong central government was tantamount to preserving individual liberties, while the Anti-Federalists wanted more power to the states and a decentralized form of government. The Massachusetts Compromise spawned from the state’s delegation’s contentions, which caused a fistfight between Federalist Francis Dana and Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry, from whose actions the term “gerrymander” was coined. The compromise allowed for amendments to be proposed at the convention when ratifying the Constitution and was created to the agreement of John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

How Presidents Were Elected Before the Twelfth Amendment

Under the original procedure for the Electoral College, each elector cast two votes, with no distinction made between votes for president and vice president. Two votes were cast by each elector, with the winner of the most votes becoming president and the runner-up becoming vice president. The two candidates chosen by the elector could not hail from the same state as that elector, preventing “favorite son” picks from their home states.

Two scenarios allowed the House of Representatives to hold contingent elections: if multiple candidates received the same number of votes – with that number being a majority of votes – or if no candidate had a majority. In the former scenario, the House would simply choose one of the two to be president. Under the latter situation, the House would choose from the five candidates with the greatest number of electoral votes. In both circumstances, each state delegation had one vote and a candidate was required to achieve an absolute majority of the votes, more than half of the total number of states to be president.

The vice presidential selection was easier: whoever received the second-largest number of votes in the election became vice president. A majority was not required, but only if the Senate had to pick a winner in the event of a tie.

The purpose of second place becoming vice president was part of the “best man” concept that the Founding Fathers had believed and sought to instill in the country. Whoever received the second-greatest number of votes was seen as second most-qualified to run the country. This concept was also markedly on-brand for the new nation who, as urged by George Washington, believed that political parties and gamesmanship would impede the work for the republic, as was the case in failed republics before. On paper, the logic for both concepts can be found, but neither concept panned out in reality.

The Election of 1800

This system worked for the first two elections – 1788 and 1792 – because George Washington was the unanimous choice for president both times. When Washington declined to seek a third term, it became apparent the electoral system needed an overhaul. In 1796, Federalist John Adams received a majority of votes from the electors, while Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson was the runner-up. It quickly became clear that having a president and a vice president of two conflicting ideologies was not going to be realistic.

The 1800 election was the location of another constitutional crisis, in which Democratic-Republicans nominated Thomas Jefferson for president and Aaron Burr for vice president. The party had secured a majority of the electors for Jefferson, but the margin was so slim, that all Democratic-Republican electors from all states needed to be on board with the picks in order to prevent another crisis. Limited communication and a bold plan of nominating candidates on a separate party ticket only led to more confusion, as electors had no way of distinguishing who was running for which office.

The Democratic-Republican electors assumed one would abstain from the vote to ensure Burr became vice president, but all were unsure of the exact plan. No electors wanted to be the one responsible for handing John Adams the White House, resulting in a scenario that was later called the Burr Dilemma: all electors voted for both Jefferson and Burr, resulting in a tie.

Thirty-five ballots ensued in the House, with neither Jefferson or Burr able to clinch a majority of votes. Alexander Hamilton helped shepherd the process through, allowing Jefferson to be elected president on the thirty-sixth vote.

The Twelfth Amendment Itself

The Twelfth Amendment reads that electors of the Electoral College are to meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for the president and vice president, one of whom, at least, is required to be an inhabitant of a state different from the other. Electors are not only required to cast their votes as decided by the population of their respective states, but they are also required to make lists of each person who received votes for president and vice president. Lists are signed and certified by and sent to the sitting Vice President, the President of the Senate.

The Vice President shall, in the presence of the U.S. House and Senate, open all certificates from the states and the Electoral College votes shall be counted. The person with the greatest number of votes within the college is elected, provided the number of votes the candidate has received is a majority of those available. If no candidate has a majority, then those on the lists of having received Electoral College votes are considered, and then a winner is selected immediately by the House of Representatives.

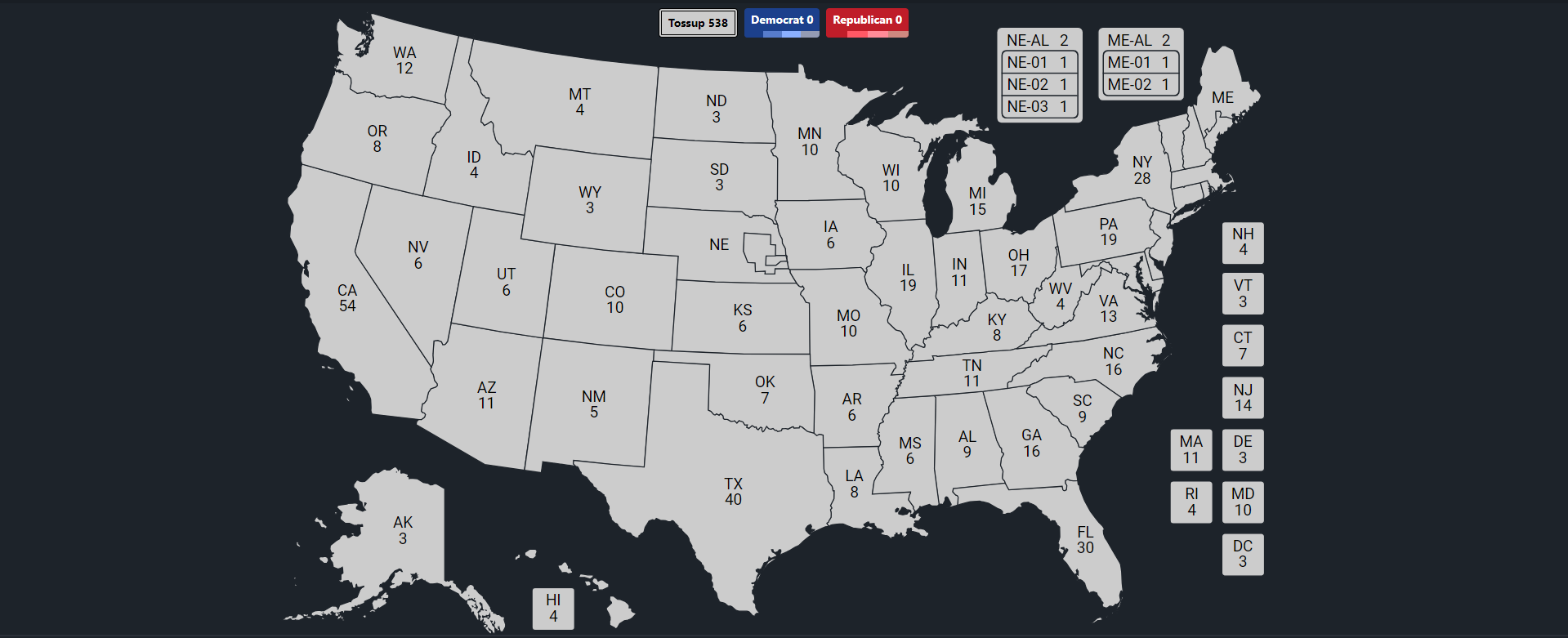

However, the vote taken by the House is a vote taken by states, rather than individual members of Congress. The congressional delegation from one state has just one vote. For example, New York has twenty-six representatives in the House, currently a delegation of sixteen Democrats and ten Republicans. In the case of an Electoral College tie – a count of 269-269 in the Electoral College – or a case of multiple candidates preventing any one from receiving at least 270 electoral votes, New York would have just one vote in the U.S. House-administered election for president, with the result likely backing a Democratic candidate.

A necessary quorum for the vote is members of the House from at least two-thirds of the states, with a majority vote necessary to name a president. The Twelfth Amendment, interestingly, does offer another backup plan if the House fails to select a president:

“And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in the case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.”

In this case, the person with the greatest number of votes, with the backdrop of a majority vote, is elected vice president. If a majority for vice president is still not achieved, then the Senate chooses the vice president from the top-two vote-receivers on the certified and signed lists delivered from the states to the Capitol. Once again, two-thirds of the Senate is required to be present to call such a quorum, and a majority vote is required to name a successor.

In the end, the Twelfth Amendment stipulates that no person constitutionally ineligible to serve in either capacity will remain in or be elected to that seat.

Results

The 1804 election was the first one to adhere to the new amendment, whereby the president and the vice president run on the same ticket and are formally elected by the Electoral College separately. Each election since then has operated under the current rules. There is no longer the possibility of multiple presidential candidates winning electoral votes from a majority of the vice presidential vote. It also ironed out the detail that no person constitutionally ineligible from serving as president is eligible to serve as vice president. There is also much more clarity of which candidates are running for which offices and ties are now much less common.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, only one election has seen the House invoke its power to select a president in the event of a tie: 1824. In this election, the Federalist Party was waning into irrelevance, as party politics and the national identities therein became inevitable in American society. Four major candidates ran, all on the Democratic-Republican line, as there was no strong opposition from the Federalist ticket. Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker Henry Clay all vied for the nation’s top job. No candidate received a majority of the electoral votes, and the House chose among the former three candidates. Jackson won a plurality of the electoral and popular votes, but the House elected John Quincy Adams as the sixth president.

This was the first of five occasions where the candidate who won the popular vote did not win the presidency, the only time that winner of the most electoral votes did not become president, and the only time the House has had to select a president in a contingent election.

1824 was also the first election in which the popular vote was fully recorded and reported. The popular vote has been decided by single-digits since 1988, the longest such streak since the states began popularly electing presidents in the 1820s. The process of moving the selection of electors to the hands of the public rather than the state legislatures was gradual, but by 1840, only one state – South Carolina – of the twenty-six at the time still selected its electors by the state legislature.