Nearly a century after the end of the Civil War, civil rights violations still occurred, predominantly in the post-Reconstruction South. The exceptionally dark time in American history gave way to the Ku Klux Klan, forms of voter intimidation and disenfranchisement, and segrega-tion. The Twenty-Fourth Amendment addresses one of those, by prohibiting both Congress and the states from levying poll taxes.

History and Origin

The period immediately following the end of the Civil War was Reconstruction (1865-1877), during which the Union North would by martial law enforce racial integration, equal rights for freedmen, blacks, and Union-supporting whites, as well as the readmission of the eleven former Confederate states.

Reconstruction saw the rise of the Radical Republicans, who not only fought for rights for black Americans, but also punitive measures against the former Confederacy and its members. They especially rose to prominence when President Andrew Johnson (D-TN) succeeded President Abraham Lincoln (R-IL) after his assassination. Johnson is often viewed as having been far too lenient in Reconstruction efforts and he is regarded as one of the worst presidents in American history due to his actions, or lack thereof, that affected black Americans for about a century after the war.

As a historical sidenote, Lincoln had selected Johnson as his 1864 running mate when the GOP switched their branding that year to the National Union Party, a means of uniting all anti-war voters and politicians to keep the hope alive that the North would prevail. Johnson, a Southern Democrat who had represented Tennessee in the U.S. Senate, was an instrumental part of that unity message. However, his election of Johnson as his running mate would go down, in some opinions, as his greatest mistake while in office, as Johnson never lived up to the “unity” expectations.

The Radical Republicans called for further and greater military occupation of the South. The faction of the new Republican Party was made up mostly of black men, the first black people in general to be elected to Congress. It was through Reconstruction that blacks and especially freedmen were able to cast ballots and even run for office.

However, the 1876 election would be the nail in the coffin for Reconstruction. In that election, Rutherford B. Hayes (R-OH) won 164 electoral votes to Samuel Tilden’s (D-NJ) 184, with 185 being needed to win. Four states – Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina – returned disputed slates of presidential electors, collectively worth twenty electoral votes. Any one of those disputes in Tilden’s favor would have made him the nineteenth president.

The election also did not fall under the rules of the Twelfth Amendment, creating a national crisis. The Senate was controlled by Republicans, and the House by Democrats. Both parties felt their own right to count the disputed slates of electoral votes. To resolve the dispute, Congress passed the Electoral Commission Act, which created a temporary, fifteen-member panel – consisting of eight Republicans and seven Democrats – to review the contested results.

The panel ruled in a party-line vote in favor of Hayes, prompting Democrats to claim fraud and theft, with some suggesting forming marching units on Washington. President Ulysses S. Grant (R-OH) tightened security to prevent this, but Democrats felt they were cheated. The 1876 election is also the second five presidential elections in which the winner of the popular vote was defeated. Hayes beat Tilden 185-184 in the Electoral College, but Tilden beat Hayes in the popular vote by a three-point margin – 50.9%-47.9%.

The Compromise of 1877, however, stipulated that with Hayes as president, the North would remove their troops from the South, thus ending Reconstruction. This led to many calling Hayes “Ruther-fraud” due to his “theft” of the 1876 election.

Point of reference: Consider the hotly-contested 2020 election. Imagine the controversy around the 1876 election during the growing pains the U.S. was experiencing at the time. 1876 is widely considered one of the most contentious elections in American history.

However, Tilden, a Democrat, vowed to end Reconstruction if elected. Likewise, President Grant’s second term was riddled with a declining lack of public support in the North for the occupation. Reconstruction was effectively doomed after this election, regardless of the winner.

Unfortunately, that was the lynchpin for the start of a dark time in the South. Southern Democrats would begin ramping up voter intimidation and disenfranchisement efforts, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and ownership requirements. Violence would also begin ramping up as segregation would be swiftly implemented. The elected Republicans in and from the South, many of whom were black, were defeated, some in fraudulent elections.

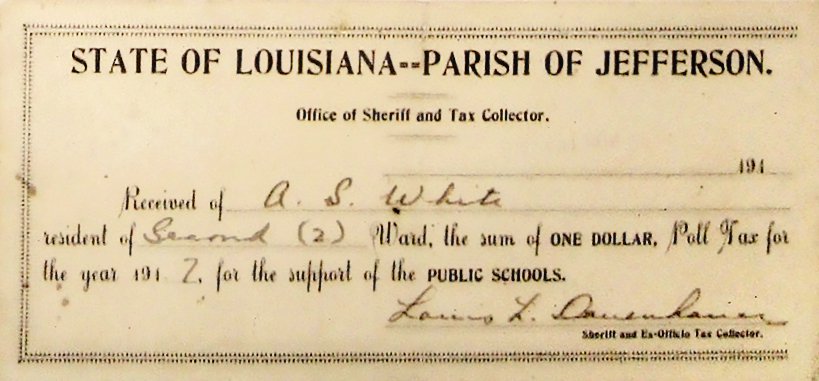

Despite the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits the denial of suffrage based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude, some states, particularly those in the South, used poll taxes, primarily, as a loophole. All voters were required to pay the poll tax, but it mostly affected the poor, who were mostly freedmen and poor whites and blacks. The Populist movement towards the end of the 1800s also helped buoy Republican electoral success in the South through fusion tickets, meaning, for Southern Democrats, the poll tax was effectively the final move to reconstruct their own political dominance.

By 1902, all former Confederate states had implemented a poll tax. Some state constitutions included provisions that required literacy and comprehension tests, which were administered subjectively by white poll workers. The grandfather clauses and “white primaries” were also used to specifically exclude black voters.

Poll taxes were abhorred by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (D-NY), but he laid off the issue when liberal Democrats lost Southern races in the 1938 midterms. FDR backed off so as to keep the Southern Democrats satisfied enough to work with him to pass the New Deal legislation.

In 1946, a bill passed the Senate 39-33, but failed to capture enough votes to invoke cloture. Senator Theodore Bilbo (D-MS) said, “If the poll tax bill passes, the next step will be an effort to remove the registration qualification, the educa-tional qualification of Negroes. If that is done we will have no way of preventing the Negroes from voting.”

This quote speaks to the genuine vitriol felt by some at the time, certainly making it an issue of race, at least in part, as other objections were held due to constitutionality.

Ratification

Congress proposed the Twenty-Fourth Amendment on August 27, 1962, with craftsmanship from Southern Democratic Senator Spessard Holland (D-FL), who had worked to ban the poll tax earlier in his Senate career.

President Lyndon B. Johnson (D-TX) called it a “triumph of liberty over restriction.”

The final House vote was 295-86 – 132-15 in the GOP Conference and 163-71 in the Democratic Caucus – with 54 abstentions.

The Final Senate vote was 77-16 – 30-1 in the GOP Conference and 47-15 in the Democratic Caucus – with seven abstentions.

Illinois became the first state to ratify, doing so on November 14, 1962, followed by New Jersey, Oregon, Montana, and West Virginia. New York was sixth to ratify, doing so on February 4, 1963.

South Dakota became the tipping-point state for ratification in early 1964, with Virginia, North Carolina, Alabama, and Texas subsequently amending. Mississippi is the only state to have rejected the amendment.

Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wyoming took no action and to date have not ratified the amendment – five of those states were at least culturally aligned with the Old South.

Text

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.”

Effects

Arkansas would repeal its poll taxes with an amendment to its state constitution in 1964, but the poll-tax language was not completely removed from their constitution until 2008. Of the five states that were immediately affected by the amendment, Arkansas was the only state to repeal its poll tax; the others retained theirs. The remaining poll taxes would be struck down by the Supreme Court in 1966 in the landmark case Harper Vs. Virginia Board of Elections. The ruling held that poll taxes, even for state elections, were unconstitutional. Federal district courts in Alabama and Texas would have their poll taxes struck down just months after the Harper ruling.

Virginia concocted an “escape clause” to the poll tax, in which voters, instead of paying the tax, would file paperwork to gain recognition of residence in Virginia. The 1965 Supreme Court decision Harman Vs. Forssenius would find this practice unconstitutional.