Election season is when we hear two phrases that carry somewhat esoteric meanings: “margin of error” being the first, and “tipping-point state” being the second. In our final Civics 101 column before the 2024 elections, we’ll discuss what these terms mean and how they relate to prognosticating and analyzing election results.

The Margin of Error

The margin of error is simply a metric for determining the confidence of a statistical study. In election season, this is a crucial standpoint of any poll conducted. It essentially expresses the possible sampling errors when a survey is performed randomly among respondents. The higher the margin of error, the less confidence one should have in the result of the study. The lower the margin of error, the more confident one can be in the survey’s results.

Margins of error are also used to showcase how accurately the information of the poll can be distributed among the general public without having to poll every single member of the public.

The exact margin is presented in a plus-or-minus fashion (stylized as +/-). Margins of error also depend on what type of statistical study is employed to prove a hypothesis. In polling, the sample means is more binary, in that a person is either voting or not voting for a candidate for office. The confidence interval can vary based on these studies, but most polling is done with a 95% confidence interval. Shortly, this means that if a survey with a margin of error of +/- three percentage points is fielded one hundred times, then the study would be expected to be true of the entire population 95% of the time, within three points of the result of the poll.

Take, for instance, the latest InsiderAdvantage poll of the presidential race in Wisconsin. The poll of 800 likely voters was conducted from October 26 to 27 and gives former President Donald Trump (R-FL) a one-point lead over Vice President Kamala Harris (D-CA). When we dig a little deeper, we find that the margin of error is +/- 3.46%. This essentially means that the result could be 3.46% off from the one-point lead for Trump, in either direction. It could mean Trump is ahead by closer to five points, or it could mean that Harris is ahead by a bit more than two. Simply adding or subtracting the margin of error from the result of the poll is a decent benchmark for figuring out who exactly has the upper hand.

Currently, the swing states are all polling within the margin of error, for the most part. This means that it’s virtually impossible to know who is winning and in what states. With high confidence intervals, we could assume that the polling is reliable enough to track the end results in these critical states to a fairly accurate result.

The type of voter sampled and the overall sample size are two important aspects of election polling. Generally, polls that sample “likely” voters – stylized as “LV” on polling sites – are seen as more accurate than those that sample “registered voters” – stylized as “RV.” The logic here is that likely voters are the ones who are simply more likely to turn out on Election Day and, therefore, are the more reliable basket of voters to poll for the state of a race.

Registered voters are generally seen as more unreliable sources because simply being a registered voter does not guarantee political participation, nor does it guarantee those voters will stick with their registered party. Polls of RVs can be valuable, however, in benchmarking a party’s support among the active rank-and-file in a certain race or state. If done correctly, these polls can help campaigns sound the alarm in states or districts where typical party support might be bleeding.

Tipping-Point States

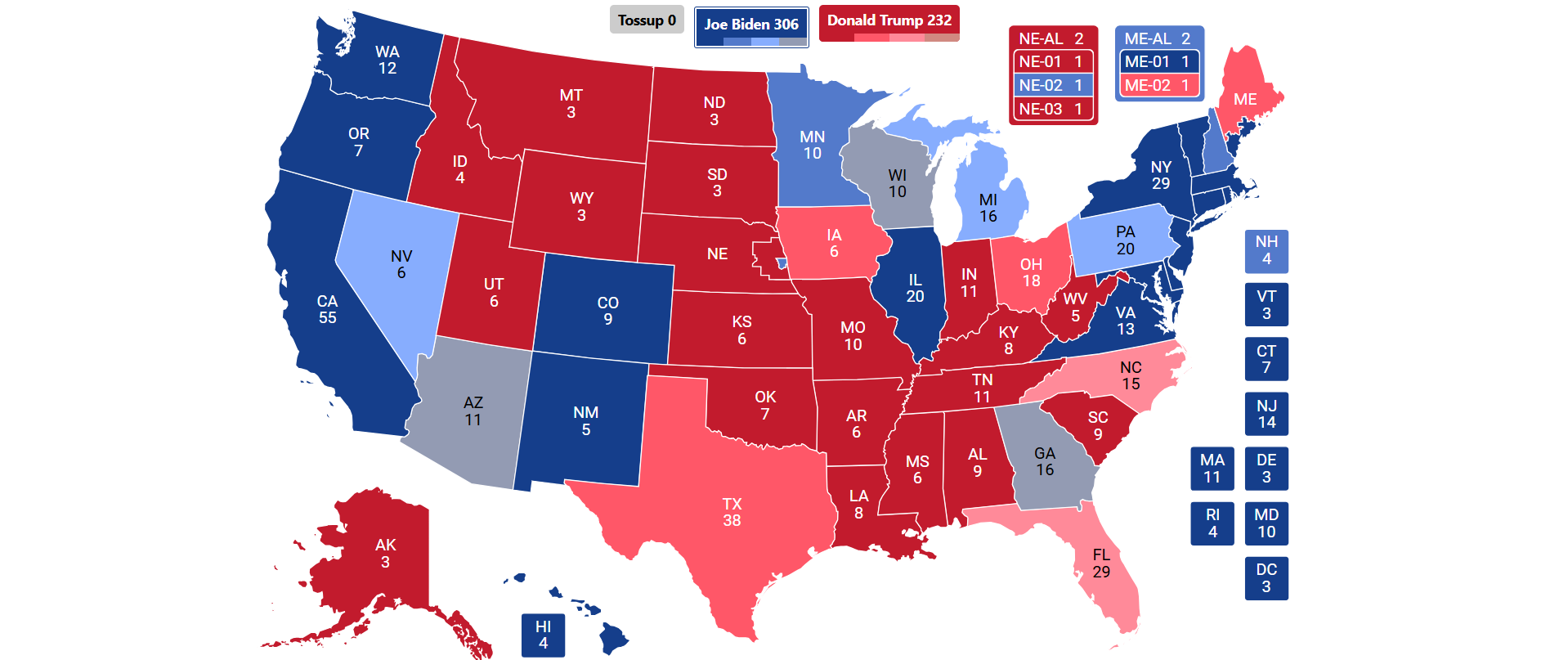

The figure of the “tipping-point state” is used by some election analysts as a way of figuring out which state was responsible for putting a presidential candidate over the magic number of 270 electoral votes. The tipping-point state is determined by ordering a list of states won by the victor from the largest margins of victory to their lowest margins. The state that puts the candidate over 270, with the winner’s margin in that state considered with respect to the winner’s margins of victory in other states, is considered the “tipping-point state.”

We’ll use 2016 as an example. Trump’s largest margin of victory on the statewide level was in West Virginia, where he earned 68.50% of the vote. This was followed by Wyoming, 68.17%, Oklahoma, 65.32%, and North Dakota, 62.96%. The list would continue, ordering Trump’s margins of victory in each state from a position of greatest-to-least. Simultaneously, these states’ electoral votes can be added to Trump’s column. The list would continue until it reached Pennsylvania, where Trump’s margin of victory was just 0.7%. However, relative to the states he won by greater margins, Pennsylvania is the one that put him over the top, making it the tipping-point state of the 2016 election.

The same can be done for Biden’s win in 2020. Biden’s greatest margin was in the District of Columbia, where he received 92.15% of the vote, followed by Vermont with 66.09%, and Massachusetts with 65.60%. This list continues until we reach Wisconsin, where Biden won by just 0.6%. With its ten electoral votes, and with other stronger margins behind it, Wisconsin was the tipping-point state in 2020.

What Will the Tipping-Point State be in 2024?

Both campaigns seem to agree that Pennsylvania is the must-win state for either of them. There are paths to victory for Harris without Georgia, Arizona, and North Carolina, and Trump could reclaim the White House without Nevada, Michigan, or New Hampshire. But Pennsylvania seems to be the key in this election, and virtually all of the major outlets, election prognosticators, and betting market savants all seem to have come to the same agreement.

But even with this in mind, it’s hard to tell if Pennsylvania will be 2024’s tipping-point state. If Trump’s win is bigger than expected, the tipping-point state could be Michigan or Nevada. The same scenario for Harris could find Arizona or Georgia as the tipping-point states.

The logic here is one with which some find issue with the tipping-point state model. The tipping-point state model assumes that margins across all fifty states and D.C. are, more or less, relative to one another, in that, if a big enough swing captures the whole country, then states are likely to statistically move in that direction based on their margins of victory for the candidate. If either candidate were to win Pennsylvania by a ten-point margin – a large unlikelihood for either campaign – it could indicate a relative swing in other states, effectively meaning that Pennsylvania would still be “tipping-point,” but that the election overall wouldn’t be remotely close. This isn’t an exact science, which makes trying to predict which state will be the tipping-point especially difficult.

It also doesn’t account for policy positions or extenuating circumstances within a state’s political landscape that could shift it right out of contention for that spot. To use a ten-point margin in Pennsylvania as an example again, such a swing could be self-contained, in that it wouldn’t translate to a nationwide swing in the direction Pennsylvania chooses. This means that it could still be a close election, but the tipping-point state would be one of the several other possible suspects.

For trivia purposes, the last time New York was considered the tipping-point state was in 1944, when Franklin D. Roosevelt (D-NY) defeated Thomas Dewey (R-NY) for his fourth and final consecutive term. New York was the tipping-point state three consecutive elections in a row: 1880, 1884, and 1888, the longest consecutive streak for any state to earn this distinction.

Colorado was the tipping-point state in both 2008 and 2012. Tennessee was Bill Clinton’s (D-AR) tipping-point state in 1992, and Michigan was Ronald Reagan’s (R-CA) in his forty-nine-state sweep in 1984.

The smallest state to ever earn this achievement is Rhode Island in 1920. Then at just five electoral votes – now at four – Warren Harding (R-OH) carried the state by 31.2%, but he won a national landslide, thereby proving the relativity of the tipping-point state statistic.