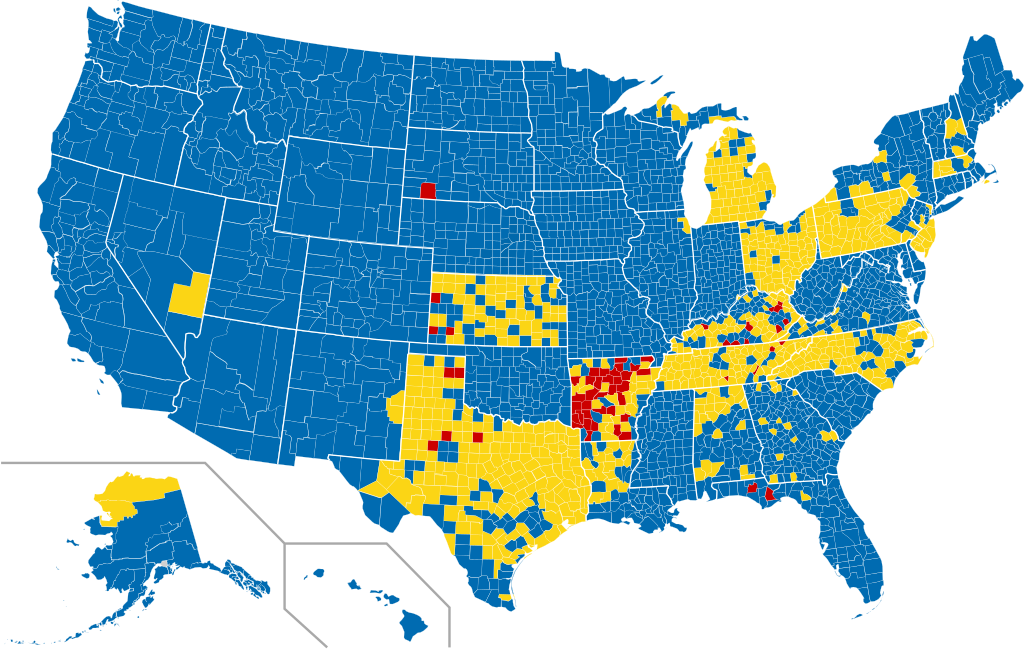

Cover photo: Alcohol control in the U.S. (Red = Dry, Blue = Wet, Yellow = Mixed)

Introduced at a particularly unique and tumultuous time in American history, the Eighteenth Amendment is responsible for having banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol in the United States. It’s also the only constitutional amendment to have been effectively repealed.

Eighteenth Amendment – History and Origin

“After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

“The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

“This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.”

The Eighteenth Amendment was the result of the decades-long temperance movement, which sought to curb the consumption of alcohol, and thereby, the large influence it had on public life, politics, and crime, all amidst a rapidly-growing nation off the heels of the Industrial Revolution.

The Anti-Saloon League (ASL) began in 1906 in Saratoga, New York, as a campaign to ban the sale of alcohol in the state. Their campaign included elements that Prohibition, as the movement at-large would later be called, would curb poverty and social problems, such as violence and immoral sexual behavior, as well as create happier families, reduce workplace accidents, and give way to new forms of sociability.

Churches were also highly influential in garnering support for Prohibition, with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union affecting some 6,000 congregations across the country. Others, such as reformer Carrie Nation, would become known for vandalizing saloons.

By 1916, twenty-three of the forty-eight states at the time had already passed laws against saloons, and some even went further as to ban the manufacture of alcohol outright.

Eighteenth Amendment – Ratification

By August 1, 1917, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution containing the language for an amendment to be sent to the states. In a 65-20 vote, thirty-six Democrats voted in favor, twelve against, while twenty-nine Republicans voted in favor, eight in opposition. By December of that year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed its revised resolution. In a 282-128 vote, Democrats supported 141-64, and Republicans supported 137-62.

What made the Eighteenth Amendment unique is that it was the first amendment to impose a deadline date. If the minimum number of states did not ratify before the deadline, the amendment would be tabled.

Mississippi became the first state to ratify on January 7, 1918, followed by Virginia, Kentucky, North Dakota, and South Carolina. Nebraska was the tipping-point state for ratification, coming in as the thirty-sixth state to do so on January 16, 1919. New York would be forty-third to ratify just two weeks later.

Connecticut and Rhode Island are the only two states to have rejected the amendment.

The better clarify the language in the amendment, Congress passed the Volstead Act, otherwise known as the National Prohibition Act, in October 1919. President Woodrow Wilson (D-NJ) vetoed the bill, but the House immediately overrode his veto, with the Senate doing the same the following day. The Volstead Act set the starting date for nationwide Prohibition for January 17, 1920, which was the earliest date permissible by the Eighteenth Amendment.

The Volstead Act

The legislation was the product of Wayne Bidwell Wheeler, the leader of the Anti-Saloon League. It was supported by Congressman Andrew Volsted (R, MN-07), Chair of the powerful House Judiciary Committee, and later the namesake of the legislation.

The Volstead Act defined how alcohol’s production and distribution would be banned. It contained three main sections.

The first section handled the previously enacted Prohibition during and after World War I. Not only did the time serve as an opportunity for reformers to get their measures passed, including Prohibition, but some suspicions of foreigners remained, as many saloons were operated by immigrants. Additionally, drinking was akin to being pro-Greman at the time, as many breweries at the time had German names.

Furthermore, the War Time Prohibition Act was less about the consumption of alcohol and more about prohibiting its usage to conserve grains. Title II of the Volstead Act defined “intoxicating beverages” as those with an alcohol content equal to or great than 0.5%.

The second section outlined how to enforce Prohibition pursuant to the Eighteenth Amendment. This included fines and jail sentences for the manufacture, sale, and movement of alcohol. It also enumerated search and seizure and enforcement powers.

However, the Volstead Act did not ban the consumption of alcohol. Citizens were allowed to possess alcohol if they were obtained before Prohibition and if drinks were customarily in the homes for occasions or company, as long as proof of purchase accompanied the beverages. Alcohol used for medicinal purposes also remained legal under the act. Physicians were allowed to prescribe one pint of spirits every ten days. Clergy could also apply for permits to provide alcohol for sacramental practices.

The third section of the Volstead Act dealt with alcohol for industrial purposes only.

The large-scale ban on manufacturing gave way to at-home winemakers, as the grapes from vineyards often could not withstand long journeys to markets where sale and manufacture were still legal.

Perhaps the largest byproduct of Prohibition, however, was the proliferation of organized crime. Major gangsters, like Chicago’s Al Capone, and Omaha’s Tom Dennison became robber barons of the drink and law enforcement’s powers were somewhat neutered by the breadth and affluence of these gangs. Speakeasies, illicit alcohol establishments, began popping up, and many “bootleggers” became sympathetic to the gangs. Even the upper echelons of society were partaking, with a Michigan State Police raid on the Detroit establishment Deutsches Haus incriminated the mayor, the sheriff, and the local congressman.

Twenty-First Amendment – Origin and Ratification

“The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

“The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

“This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by conventions in the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.”

Due to a lack of societal acceptance, the sheer logistical project of enforcement, and the rise of powerful criminal organizations made Prohibition an experiment worth ending. On February 20, 1933, almost fifteen years after the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified, the Twenty-First Amendment was ratified. It remains the only amendment that specifically repeals a prior amendment.

What also makes this amendment unique is that it is the only one to have been passed via state ratifying convention. Article V of the Constitution permits the House and Senate, when they deem necessary, to call a convention for the purpose of dealing with a specific issue, allowing Congress to effectively bypass certain levels of state sovereignty. The method calls a convention of state legislatures to deliberate and vote on the proposed amendment as written, rather than giving it to the states legislatures. Ratifying conventions also elect delegates by a popular vote for the issue, rather than going through the regularly-elected state legislatures. The convention method requires the same three-fourths majority to approve, as it does in the typical legislative method.

Michigan first voted to ratify on April 10, 1933, followed by Wisconsin, Rhode Island, Wyoming, and New Jersey. Utah was the tipping-point state, ratifying in December that year. Maine and Montana subsequently ratified. South Carolina rejected the measure unanimously at its convention, while North Carolina rejected the convention altogether.

Dry and Wet Counties Today

Even though there isn’t much federal oversight of how alcohol is manufactured, sold, and moved as there once was, states can still afford their counties and municipalities to enforce their own alcohol laws.

Thirty-three states have laws that allow localities to prohibit the sale, consumption, and possession of liquor. New York is one of these states that are “wet” by default, but have provisions for localities to exercise a local option by public referendum to go dry and to what extent. Most states defer the matter to public referenda, but some allow municipalities to enforce laws stricter than those of the state overall.

Seventeen states prohibit “dry” counties overall. In states like Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, and Maryland prevent localities from enforcing alcohol laws greater than those of the state. As a result, no “dry” communities can be formed in these states. States like Hawaii only allow local control of alcohol in terms of licensing of manufacture and sale.

While Missouri law prohibits municipalities from going “dry”, incorporated cities can by public referendum, although none have done so.

States like Montana that have Native American reservations cannot enforce liquor laws on said lands, as reservations are entirely under the purview of the federal government.

In New York, eight towns are completely “dry” and thirty-nine are partially “dry”. Dry towns include Caneadea (Allegany County), Lapeer (Cortland County), and Berkshire (Tioga County). Several towns do not allow off-premises consumption, while others bar on-premises consumption, except in year-round hotels.

There are twenty-two partially “dry” counties in New York that have varying specific rules for special on-premises consumption. The Town of Wilmington (Essex County) is a “dry” county, except for on-premises consumption at race tracks and outdoor athletic fields and stadiums where admission fees are charged.

Only two states – Kansas and Tennessee – are “dry” by default and localities must pass by referenda their ability to sell alcohol subject to state laws.