This week, we’re pausing our in-depth autopsy of the 2024 election results to discuss a timely topic: the certification of the Electoral College.

Despite the population voting for president in November, they’re not voting directly for their preferred candidate. Instead, they’re voting for a slate of electors who are pre-pledged to back the nominee who carries their state. These electors make up the Electoral College and have spent the last few weeks in the process of formally certifying Donald Trump’s (R-FL) and Kamala Harris’ (D-CA) wins in the recent presidential election.

Background on the Electoral College

One of our very first Civics 101 columns discussed the Electoral College fully, as well as the Twelfth Amendment – which outlined how our elections are constitutionally administered – in a separate article.

The Electoral College is composed of the collective number of U.S. House Representatives and U.S. Senators allotted to each state. The House represents the states proportionally, with larger states receiving more congressional districts, and, therefore, more electoral votes. California has the largest batch at 54, while six states are tied for the lowest and lowest-possible number, just 3 electoral votes. Congressional districts are added or eliminated based on interstate population shifts pursuant to the results of the U.S. Census, conducted every ten years. States whose population shifts did not qualify for the addition or removal of a congressional district – and an electoral vote – redrawn their lines to accurately reflect intrastate population shifts.

The Senate, meanwhile, represents the states equally, with each receiving two Senators, regardless of population or size.

A state’s Electoral College vote tally is a combination of these two figures. For instance, New York has twenty-six congressional districts, plus the two Senators, making for twenty-eight electoral votes.

The College has 538 votes available: 435 congressional districts, 100 Senators, and three electors from the District of Columbia, who have participated in every election since 1964, never one backing a Republican candidate.

The goal for either candidate then is to reach a majority of the votes available, which comes out to the magic number of 270. The first candidate to reach this number wins the election.

Only two states, Maine and Nebraska, award electoral votes based on the popular vote-winner in each congressional district in the state. Nebraska’s first split came in 2008, the first occurrence since the state shifted from its winner-take-all process in 1992. Maine’s first split came in 2016, after adopting the process in 1972. The 2020 election marked the first time both states split their votes in the same election, a historical anomaly that was repeated this year.

Who Are the Electors?

Once the votes have been tallied and winners and losers have been called, the process is then kicked, not to Congress, but to the states. Although the process is somewhat ceremonial, it does uphold the institution of the Electoral College and is a vital part of the election process that ultimately concludes with the certification of the results by Congress, followed by Inauguration Day on January 20.

Assuming there are no faithless electors, a topic we’ve also discussed in a dedicated Civics 101 article, the final electoral vote count should exactly mirror the results of the election. In this case, Trump should win 312 electoral votes to Harris’ 226, the lowest number of electoral votes for a Democrat since 1988.

Thirty-seven states and D.C. require electors to vote for the pledged candidate, while many have laws that remove, replace, and/or otherwise penalize electors who attempt to vote apart from the election results. However, while faithless electors are relatively rare, the tumultuous 2016 election culminated with seven faithless electors, with Trump losing two and Hillary Clinton (D-NY) losing five.

With the results fully certified as of Tuesday night, no faithless electors emerged, nor were there any attempts, as far we can see.

The electors for the College may be state elected officials, party leaders, or residents of a state that have a personal and/or political connection with their party’s presidential candidate. The slates of electors are determined before the election by both parties, with only one slate of electors sure to cast their votes in December.

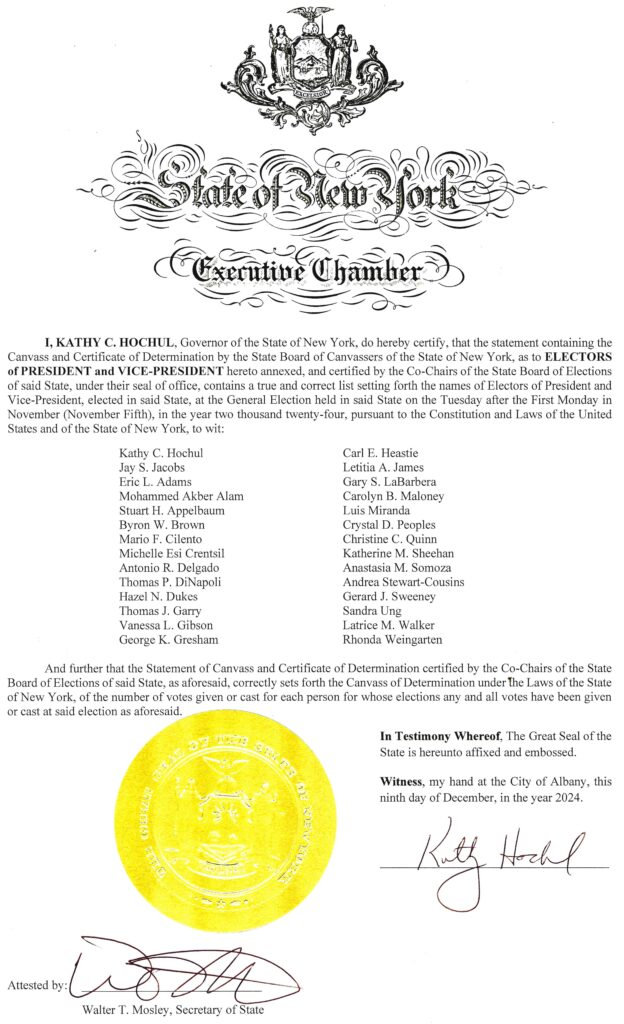

Since Vice President Harris won New York, the twenty-eight electors all backed her. Notable names include Governor Kathy Hochul (D), New York City Mayor Eric Adams (D), State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli (D-Great Neck Plaza), Attorney General Letitia James (D), Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie (D-Bronx), and even Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers. These figures, as well as the other electors, all casted their votes for Harris.

Had Trump won New York, an entirely different slate would have voted for him.

Notable figures include Suffolk County Republican Party Chairman Jesse Garcia (R-Ridge), Suffolk Conservative Party Chairman Michael Torres, Senate Minority Leader Rob Ortt (R-North Tonawanda), Assembly Minority Leader Will Barclay (R-Pulaski), Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman (R-Atlantic Beach), Assemblyman Karl Brabenac (R-Westbrookville), former Congressman Lee Zeldin (R-Shirley), and New York State Republican Committee Chairman Ed Cox.

The Certification Process

After the election results are tallied, the process begins with filing the Certificate of Ascertainment, which each state is required to file. The certificates are due six days before the electors are scheduled to meet. This year, electors met in their respective state capitals on Tuesday, December 17.

The only rules of the certificates are that they are signed by the governor and include the state seal.

The Certificate of Ascertainment itself contains the slate of electors, by name, for each candidate, including third-party and minor candidates. The certificate will note which slate received the largest number of votes, with the number printed alongside the winning slate. However, not all states include the names of the presidential candidates themselves on the certificates.

Each elector adds his/her signature to a Certificate of Vote, with which the Ascertainment is paired.

Once the votes are formally cast, seven duplicates are made. The first pair of certificates go to the vice president – the president of the Senate – who will preside over the final count and certification of the election results by Congress in January. The vice president, in this case Kamala Harris, will open fifty-one envelopes – all states and D.C. – to read aloud the winners of each state in the presence of a joint session of Congress. The vice president also receives the pairs of certificates from each state. This year, the deadline to receive the pairs of certificates from each state is December 28.

Another two copies are sent to the Archivist of the United States – an appointed position currently held by Colleen Shogan – at the National Archives and Records Administration with the same December 28 deadline.

The secretaries of state each keep two copies of the pairs, one in the event that the original pair does not reach the Archivist or the U.S. Senate, and one for public display and inspection.

Another pair goes to the U.S. District Court Judge for the respective state, while two extra copies are made as emergency backups in the event the other copies or the originals are lost or destroyed.

Electors also receive copies of the documents.

In late December, the Archivist will transfer all the pairs of certificates to Congress, which will be followed by the joint session of Congress on January 6, 2025. Here, it is permissible for members of Congress to challenge the results of each state, something that has occurred in four of the seven elections this century: 2000, 2004, 2016, and 2020. A challenge to a state’s result requires one House member and one Senate member to submit the objection. If that occurs, the two chambers of Congress separate and have two hours of debate and to vote on whether to continue the count. Both chambers must vote by a simple majority (50% + 1) to agree with the objection for it to stand. If not, the objection fails.

If no candidate receives 270 electoral votes, either through successful congressional objections, faithless electors, or third-party candidates, the Twelfth Amendment kicks in, empowering the House to select the president (one vote per state), and the Senate to choose the vice president (one vote per Senator). In the case of the House, the top-three vote-receivers are the only candidates from which the House can choose. If this were the case this year, Trump, Harris, and Green Party candidate Jill Stein – who took third place with just 0.55% of the national popular vote – would be in contention for the presidency.