While the country and the world are still reacting to President-elect Donald Trump’s historic comeback, it’s important to note that other American politicians have made once-unthinkable comebacks in politics under similar, or even more daunting, circumstances than Trump’s re-election. Last week, we discussed the first, and until this election, the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms, Grover Cleveland (D-NY), who also had his own comeback story.

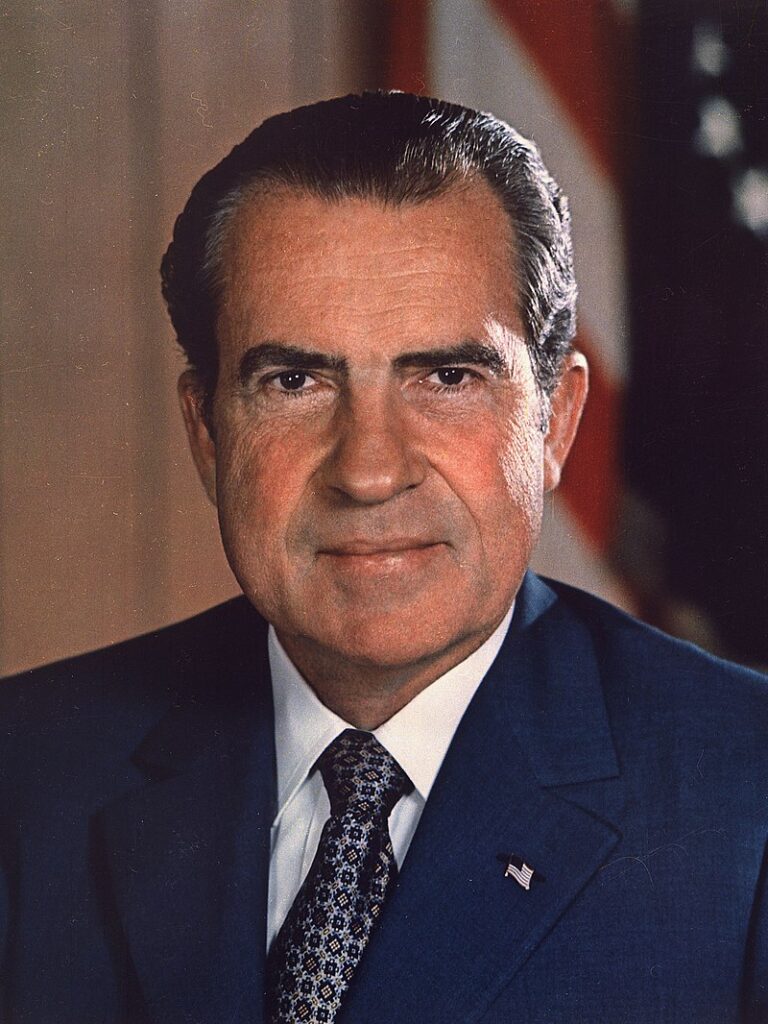

But there’s an even wilder comeback story from perhaps one of the most divisive times in our country’s history. That comeback was of President Richard Nixon (R-CA).

The 1960 Presidential Election

The 1960 election was historic for many reasons. Alaska and Hawaii had just become states the year prior and voted for the first time in a presidential race. This was the first election in which both major-party candidates were born in the Twentieth Century. John F. Kennedy (D-MA) became the youngest person elected to the presidency at forty-three years old. Moreover, he was the first Irish Catholic elected president. Kennedy’s victory in this hard-fought contest would bring an unparalleled edge to an American political dynasty that seems to have culminated in Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s abandonment of the party.

This election was also the first in which a presidential debate was televised, an aspect that historians agree helped swing the election to Kennedy, as he appeared more astute and collected, while Nixon appeared unkempt, shifty, and inexperienced in the nascent television set. Despite this, radio listeners agreed more with Nixon, while television viewers were more impressed with Kennedy.

The 1960 election was also important as it restructured campaign strategy in some ways. Richard Nixon worked to visit every state, while Kennedy focused on the battlegrounds. The result was a sizable margin in the Electoral College for Kennedy, 303 votes to Nixon’s 216. However, it was a photo-finish in the popular vote, with Kennedy winning by just over 100,000 votes out of more than sixty million cast. The election would also see the losing candidate carry more states than the victor for the first time in history, and would not be repeated again until 1976. In fact, Nixon came within five states and just about 80,000 votes of winning the presidency.

Historians also give credence to the theory that Alaska proved to be the most decisive state, as Nixon exhausted his resources in campaigning in all fifty states. Alaska did go to Nixon, albeit narrowly, but his time there is interpreted to have cost him the election, as he could have campaigned in Illinois and Texas, two close states that would have secured him the White House. Nixon was pressured to contest the results of the election, as Kennedy’s running mate, eventual President Lyndon Johnson (D-TX), had considerable clout in Texas, alongside the powerful Chicago political machine. Nixon ultimately did not contest the race, but an audit did swing Hawaii to Kennedy.

This sets the stage for some familiar overtones we heard in this election, but the contentious election was more than just numbers. Key issues included Civil Rights, segregation, the Vietnam War, and the space race with the USSR, among other topics.

Nixon’s career didn’t appear over at first, as the election was still close, and he had considerable name recognition after serving as Vice President under President Dwight Eisenhower (R-KS) for his two full terms.

But Nixon’s comeback started with an unlikely figure that appeared to have ended his public service career altogether: himself.

Nixon’s “Last Press Conference”

California, like many other Western states for a large period of the 1900s, was considered a “red” state, and the Western front was seen as an impenetrable Republican fortress that gave them the floor they needed to compete nationwide. The only Western states Nixon had failed to carry in 1960 were Nevada and New Mexico, which were still remarkably close. California very narrowly went to native son Nixon, but it was on a Republican voting streak that would not be broken until 1992.

California seemed like the easiest rebound for Nixon. Not only would it amount to political survival, but governing the one of the country’s largest and most influential states would easily be a catapult back to the presidential map, for a likely 1964 rematch with Kennedy.

However, embarrassingly Nixon lost his home state by about five points to Governor Pat Brown (D). Democrats had poor electoral prospects in the Golden State, with Brown being the only Democrat to govern the state since 1938, and before that, 1894. Brown had also not taken the campaign seriously until late in the season, by which time, nearly all polls and pundits forecasted a Nixon win. Brown managed to close the gap in the last few days, but Nixon was still favored to win.

In his concession speech the following morning, Nixon stated his discontent with the media, whom he accused of siding with his opponent.

“Now that all the members of the press are so delighted that I have lost, I’d like to make a statement of my own,” he told about one hundred reporters at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. “I leave you gentlemen now. And you will now write it. You will interpret it. That’s your right. But as I leave you, I want you to know—just think how much you’re going to be missing. You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore. Because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

Governor Brown would then lose the 1966 election to Ronald Reagan (R-CA).

Nixon seemed to be his own victim, taking himself out of the national spotlight and effectively giving up.

Six years later, Nixon would win the landmark election of 1968.

The 1968 Election

Tensions had hardly been diffused since the 1960 election. President Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963, seeing Lyndon Johnson ascend to the presidency and win a massive landslide in 1964, campaigning primarily on Civil Rights and continuing tenets of the Great Society. He defeated Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ), who won just six states. Johnson’s landslide is the last in which many Rocky Mountain and Great Plains states, as well as Alaska, have backed a Democrat for president.

But Johnson was incredibly vulnerable due to the country’s shifting views on race, as well as mass-opposition to the Vietnam War, nervousness of nuclear escalations from the Cuban Missile Crisis, to name a few. Johnson barely survived the New Hampshire Primary, suspending his campaign and kicking the contest to an open primary. Johnson would be the last incumbent president to decline re-election until Joe Biden (D-DE) did so in July.

The Democrats were in need of a quick reshuffle, going with Vice President Hubert Humphrey (D-MN). Segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace, after much suspense surrounding a Democratic or Independent run in 1964, ran on a “states’ rights” platform as it pertained to racial integration. He only carried five Southern states, the last time any Independent candidate would win any electoral votes and/or states in a presidential contest.

The 1960s were also one of the most tumultuous periods of modern American history, as the assassinations of both Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Sr. (D-MA) and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. only did more to fan the flames of an already divided country. Moreover, college campus protests of the Vietnam War sparked violent confrontations with police, even escalating at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, oddly the same locale of the 2024 DNC.

But Nixon was able to claim the divide to his advantage, campaigning on ending the Vietnam War and restoring “law and order.” Analysts believe that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s (D-NY) New Deal Coalition had collapsed with this watershed election.

Nixon would win 301 electoral votes with thirty-two states and a razor-thin popular vote margin. Humphrey won 191 electoral votes, with Wallace taking forty-six.

But Nixon wasn’t quite finished writing his own “art of the comeback.” His close, yet concrete, 1968 victory was already a phoenix-from-the-ashes moment for him, but it was hardly enough to prepare the nation for one of the most lopsided elections in our history.

The 1972 Election

Nixon campaigned on the strong economy and foreign affairs successes, while Senator George McGovern (D-SD) called for an immediate end to tensions in Southeast Asia, as well as a pitch of a guaranteed minimum income (GMI). Additionally, McGovern’s campaign was damaged early by mental health revelations of his running mate, Senator Thomas Eagleton (D-MO). Eagleton was replaced by Sargent Shriver (D-MD) after just nineteen days of the campaign.

But the fallout for McGovern was more than that. Analysts might be correct in theorizing that the 1968 election was the collapse of the New Deal coalition that guaranteed Democrats electoral success during the 1930s and 1940s. Since Nixon was making good on his promises, it was easily foiled by worries that McGovern’s platform was simply “too radical.”

Nixon won in a landslide victory. He carried 60.7% of the popular vote, the most for any Republican candidate in history, and swept forty-nine states, losing only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Nixon became the first two-term vice president to win two terms as president and is the last Republican to have carried Minnesota in a presidential race.

Only seven states were classified as “close” this cycle – those whose margins were within ten points for either candidate – compared to thirty-four states in the same column in 1960 and twenty-eight states in 1968. Nixon’s closest state was Minnesota, which he carried by 5%, a decent margin for a battleground, followed by Rhode Island, South Dakota, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Maine’s First Congressional District.

In short, it was a blowout of historic proportions that seemed almost off the table completely when Nixon lost the 1962 California governor’s race in a humiliating fashion and seemingly retired from politics altogether.

Of course, Nixon’s legacy would forever be tainted by the Watergate scandal, but it doesn’t take away from the massive political movement that Nixon was able to spearhead, destroying a once-monolithic coalition and winning one of the most lopsided elections in history in one of the most divisive times of our country.

History in the Making?

We offer this in-depth analysis of a political comeback in the wake of Donald Trump’s. Although not quite the landslide Nixon pulled off in 1972, Trump’s win this year is more on par with Nixon’s 1968 win. Trump technically exceeded Nixon’s electoral and popular vote counts, but there was no notable third-party candidate on the ticket this year.

But there are similarities. Trump appears to have broken a valuable Democratic coalition that appears to be on heavily borrowed time, he left Washington a pariah with virtually no political path forward – although he never took himself out of politics like Nixon did – combined with investigations and assassination attempts.

Brit Hume, a political commentator of ABC News, now with Fox, reacted to Trump’s comeback on election night, comparing it to Nixon’s exact trajectory we’ve outlined. Hume believes that Trump’s “extraordinary” comeback “surmounts” that of Nixon’s.