As the upper chamber of the U.S. Congress, the Senate provides states with equal representation; each state gets two. Senate terms are six years long with no term limits for incumbent. Once a body more reflective of the political whims of a state’s ancestral politics, the Senate has since grown to mirror presidential-level results very closely, resulting in the lowest number of states with split delegations since the direct election of Senators began in 1913.

Before the Seventeenth Amendment

Originally, members of the U.S. House were elected popularly, as House districts are drawn to be roughly equal in population. Senators, on the other hand, were elected by the respective state legislators, who in turn were elected popularly. The logic behind this was that the Senate was essentially the state’s lobbying arm in the federal government. Since local elections can swing wildly between election years, in tandem with presidential and midterm environments, it was assumed that the people would select local elected officials who they believed would best represent their districts. Those state legislators would then confirm the Senators to send to Washington.

With the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, Senators began being elected popularly. The logic behind this move was to end pay-to-play systems in which allies of a state’s political party and friends of the capital in general could easily ascend to Washington.

Since then, the Senate map has evolved immensely over the various political eras the country has experienced. It begs the question of what kind of bargaining power certain parties in Washington would still have today if the Seventeenth Amendment was never ratified. Republicans held the Senate in New York from WWII until 2018, with a few years of Democratic control in between. Theoretically, a Republican, or more moderate Democrat, could have represented New York in Washington as early as the last election, which was in 2016.

“Split” Delegations

A split delegation is simply one that is shared between two parties. Split delegations are generally evident of elected officials who represent their states accurately in the eyes of constituents, as well as those of healthy competition.

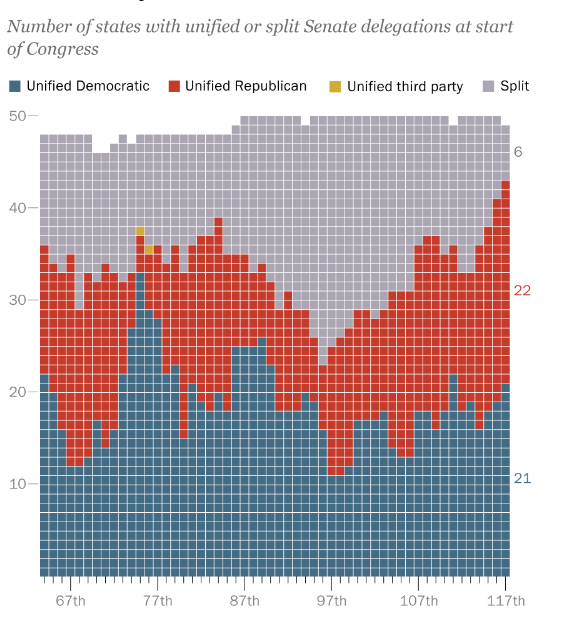

Split delegations became more prominent in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1980, twenty-seven states had split delegations, and there were never less than twenty states with split delegations from 1973 to 1994.

As recently as 2014, Louisiana, Arkansas, Alaska, South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois had split delegations. Red states like Indiana and Montana had two Democratic Senators each, while as recently as 2008, blue states like Oregon, Minnesota, and New Mexico had Republican Senators.

Now, only five states have split delegations, the lowest since the direct election of Senators began in 1913. Maine, Montana, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin have one Republican Senator and one Democratic Senator each. Technically, Angus King (I-ME) and Joe Manchin (I-WV) are Independents, but caucus with the Democrats. The same can be said for Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT), although those states have Democrats occupying the other seats.

A Decline in Competition

The rise and fall in split delegations has always been cyclical, but the current dearth of cooperative Senate representation is unparalleled in American electoral history. Many assert that the downturn in split delegations is due to an increase in partisanship and a decrease in split-ticket voting.

Regarding the aforementioned states, Democrats flipped eight seats in the 2008 elections. Only one of them, Alaska, split their tickets, backing Mark Begich (D) for Senate and John McCain (R-AZ) for president. In 2012, Indiana backed Mitt Romney (R-MA) for president, but Democrat Joe Donnelly flipped the seat blue. That same year, Democrats were re-elected in North Dakota, Missouri, and West Virginia as Romney carried those states, while Republican Dean Heller was elected in Nevada despite having backed Obama on the same night.

2016 was a historic election night in many ways. However, the Senate elections were the first in which each state’s Senate elections mirrored their respective presidential results exactly.

2018 was no exception to typical anti-incumbent president midterm energy. Four states that backed Trump two years prior ousted incumbent Democrats, while Nevada ousted Senator Heller; Nevada had backed Hillary Clinton (D-NY) in 2016. Arizona was the only outlier, having backed Trump in 2016 but electing Sinema that year.

In 2020, Maine’s Susan Collins (R) was the only Senator to deliver a Senate result opposite that of the concurrent presidential vote. Every other state opted for President and Senator of the same party.

Compare these results to those of 2000. Bush-won states that elected Democratic Senators in Missouri, Florida, Nebraska, North Dakota, and West Virginia. While Gore-won states elected Republican Senators in Vermont, Maine, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania.

These results only become more spread out the further back in history we go. We’ll look at 1976 since it was a close presidential election where the states were mostly evenly divided between Jimmy Carter (D-GA) and Gerald Ford (R-MI). This election also skips outliers from the Reagan landslides of 1980 and 1994 and third-party performances from Ross Perot (I-TX) in 1992 and 1996.

Democrats won Senate races in ten states that Ford carried, while Republicans won Senate races in four states that Carter carried.

Not only have states begun to mirror presidential results at face value, but they have also begun to mirror them in terms of margin as well, showing that candidate quality does not necessarily have as much of an effect on overperformance or underperformance as it once did.

Because of increased partisanship, the Senate’s alternating maps put certain states in the throes of partisan politics on a regular basis.

Because of six-year staggered terms, Senators find themselves running in a presidential year in one election, followed by a midterm year six years later. This effectively guarantees competition on paper, as a state that safely elects one party in a presidential year could find itself in a competitive race in a tough midterm environment.

The Current Split Delegations and 2024 Landscape

The five states with split delegations are political anomalies in and of themselves.

Maine is known for its intrinsic libertarianism, classical Yankee Republicanism, and ardent opposition to certain national trends. One of the most bipartisan Senators of several sessions of Congress, Susan Collins won re-election by ten points as Joe Biden (D-DE) carried the state by nine points in 2020. Notably independent as well, Maine has given two terms – so far – to Angus King, who served two terms as governor as an Independent. Despite caucusing with Democrats in the Senate, King does not run on their ticket in elections.

Montana is known for a strict east-west divide, with the eastern two-third being friendly to Republicans as a mostly-agrarian landscape, and the western third being heavily Democratic, unionized mining towns. Democrats have occupied at least one Senate seat in Montana for most of its statehood, with Republicans having last held both simultaneously in 1911. Senator Steve Daines (R) made history in 2020 by becoming the first Republican ever re-elected to the U.S. Senate from Montana’s Class II Senate seat.

Incumbent Jon Tester (D) is a regular overperformer, but he’ll have to generate roughly twenty points of crossover support to retain his seat in a state that is likely to go Trump by about that margin. In every election since 1972, Montana has swung against the incumbent president, virtually erasing any margin for error Tester originally might have had. If Tester does somehow pull this out, it would be an electoral feat for the current age.

Ohio was once the quintessential swing state, but Democrats have suffered geography problems at the hands of the Trump era, as former working-class, mostly union households have left the party in droves. Not only can the Democrats not reliably count on Ohio’s electoral votes anymore, Democrats will have to try much harder to retain this seat for incumbent Sherrod Brown (D) this year.

West Virginia was once an ancestrally Democratic state full of union, blue-collar workers from the coal and steel industries. Joe Manchin barely got by in 2018, vastly underperforming the national environment, mostly to a weak opponent. However, running against a ticket that is likely to back Trump by at least forty points was seen as a virtually impossible task. Manchin opted not to run for another term, essentially guaranteeing a Republican gain in the closely-divided chamber.

Finally, Wisconsin is about as closely divided a swing state as it gets. Mostly partisan to begin with, Wisconsin re-elected Ron Johnson (R) in 2016 as Trump also carried the state, becoming the first Republican to do so since 1984. Johnson survived a tough re-election bid in 2022, but rode the weak GOP environment to another term. Wisconsin’s other seat, held by Tammy Baldwin (D), is on the ballot this year, and while she should be in danger, on paper, she might fare well despite the highly competitive presidential contest brewing there.

Republicans are bullish on businessman Eric Hovde’s (R) chances this year, but Wisconsin might continue its streak of swing state politics this year.