What is Gerrymandering?

The process of gerrymandering is one that is of perennial interest, from the Town and County level, all the way up to the federal level. A problem with which both parties try to blame each other, gerrymandering can have a significant effect on the balance of power in a government body.

Simply put, gerrymandering is the drawing of legislative boundaries to the advantage of one party or the disadvantage of another.

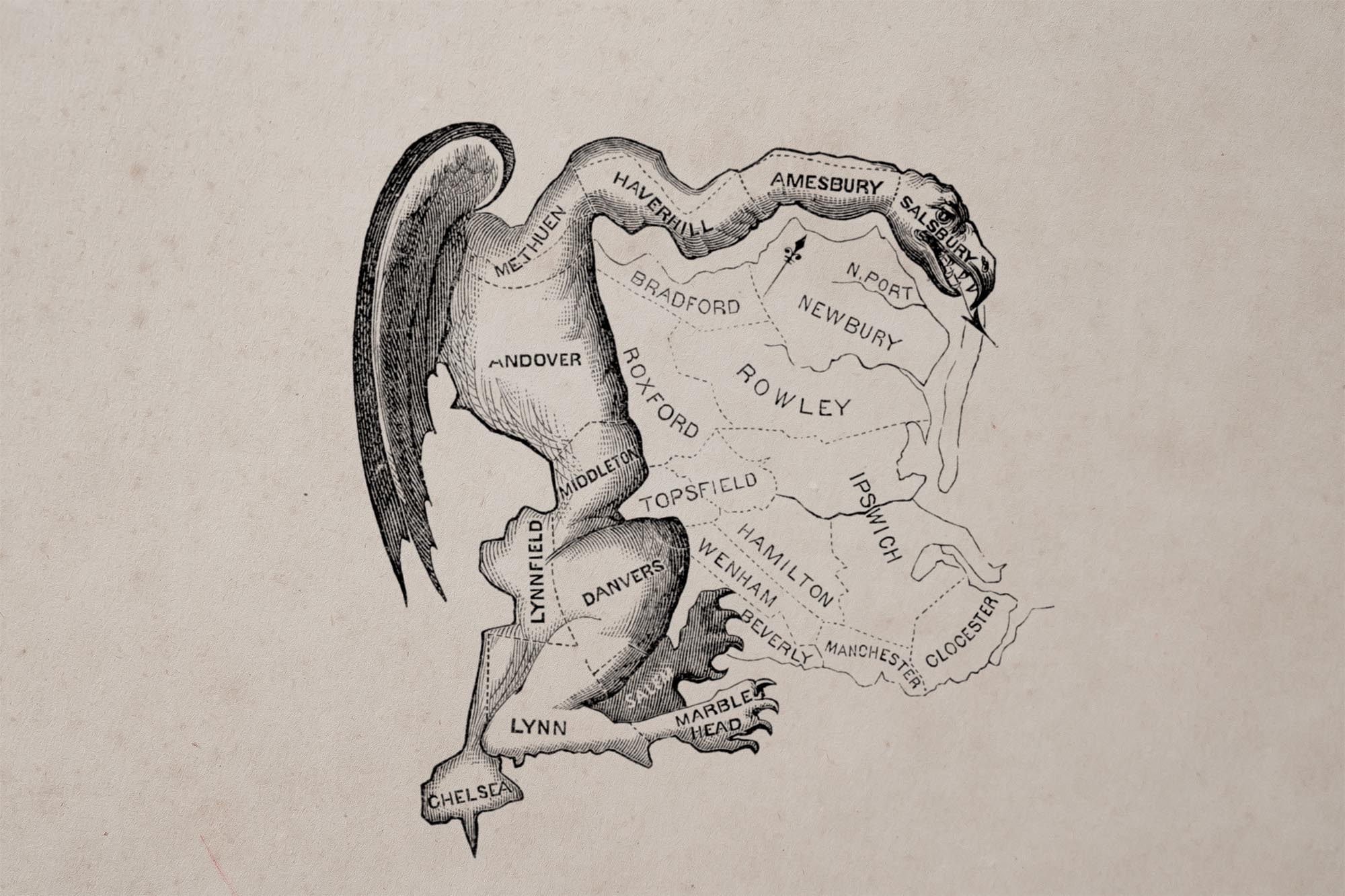

The term “gerrymandering” is a portmanteau of the words “Gerry” and “salamander.” The term was coined in 1812 by The Boston Gazette in response to Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry’s proposition of state Senate districts. Although Gerry vocally opposed the practice, he signed a bill into law that drew Massachusetts’ Senate districts to benefit the Democratic-Republican Party. One of the districts in the Boston area was likened to a salamander. A political cartoon was drawn to depict a mythological dragon (pictured above). The cartoon accompanied the name, and thus, the term was born.

Gerrymandering can be done on bases of partisan registration, race, ethnicity, income, education levels, or geography.

Methods of Gerrymandering

There are several methods that parties will use to tilt a map to their advantage or create a much more unfavorable map for their opponents.

Cracking – Cracking is when an area of electoral significance is divided between multiple districts to dilute the area’s influence. This is commonly applied to cities or metropolitan areas, as these tend to be large population centers of a state that could provide one party with multiple easy wins. A current example is TN-05, in which heavily-Democratic Nashville is divided between three districts. A once solidly-blue district, TN-05 is now represented by Congressman Andy Ogles (R), who flipped the district after Tennessee Republicans approved the map in 2021. As urban centers tend to be heavily Democratic today, cracking cities is a common gerrymandering tactic of Republicans in certain states.

Packing – Packing involves fitting as many voters of a certain bloc into one district in order to reduce concentration of said bloc across the state. An example of this would be creating highly-concentrated majority-minority districts. Although such districts would abide by some tenets of the Voting Rights Act, such districts could be ruled a gerrymander if the influence of a minority voting bloc is tampered down by the boundaries. Demographics who vote monolithically could easily sway elections if districts are not packed.

The Voting Rights Act is often used as a legal basis for challenging gerrymandered maps. Shortly, the Act requires districts to accurately represent the demographics of the state in compact districts that do not split like communities. The Act was invoked in overturning maps approved in 2021 for Alabama and Louisiana. Both states were required to draw a second black-majority district to represent the state’s population, although Louisiana’s new map (drawn and approved by Republicans) is now facing alternative claims of gerrymandering, despite the map’s satisfaction in the eyes of the Supreme Court.

Unpacking – Unpacking is essentially the opposite of cracking, in which a party will split up an area’s electoral influence to spread across multiple districts. A notable example is what Democrats did in Nevada in 2021. Previously, the state had one solid red district, one solid blue seat, and two swing seats. Las Vegas’ large Latino and young populations were “unpacked” to spread to three districts. While it made the formerly solid blue seat more competitive, it shored Democratic aspects in the swing seats. Consequently, Democrats were able to ride the 2022 environment to retain all three seats in the midterms.

Hijacking – Hijacking is when one party draws two districts in a way that requires two incumbents to primary each other, guaranteeing one’s elimination. This method is much more concerted, as it can be used to target representatives whom state leadership would like to see lose re-election. The new boundaries would have to be drawn in such a way that ensures one incumbent’s loss, such as a voting record that does not align with the new district’s interests or one in which constituents do not identify with a “new” incumbent.

Kidnapping – This one is perhaps the least effective method, as it involves moving an incumbent’s home address into another district. Re-election is not impossible, but it can complicate an incumbent’s efforts, as politicking with a new voting base might not be feasible before an election. Likewise, a primarily urban district might be redrawn to encompass more suburban or rural areas, creating a more difficult environment for re-election, especially in the face of challenging national moods.

Offense – One party decides to go on the offensive, attempting to create as unfavorable of an environment as possible for the opposite party.

Defense – One party decides to play it safe and shore up vulnerable opponents rather than create new opportunities for themselves.

What Does a Party Need to Gerrymander?

On the Town, County, or state level, legislative boundaries typically align with the seat of the applicable form of government. In New York, maps are drawn by the Independent Redistricting Commission (IRC). However, unlike IRCs of other states, New York’s is considered “fantasy-league,” as it was approved by ballot measure when Democrats did not have a trifecta in Albany. For the IRCs inaugural redistricting session in 2021, Democrats had gained a trifecta in state government. The rules stipulate that the IRC can submit two maps to the state legislature for approval, after which if the legislature rejects them, they can draw their own map. This is exactly what happened in 2021, when Democrats attempted an aggressive gerrymander against Republicans. The map was struck down by the state’s highest court, resulting in a compromise map drawn by special master Jonathan Cervas. The map was challenged late last year, which resulted in a minimal-change proposal by the State Senate.

Most states leave their redistricting responsibilities with the legislatures. Thus, if a party has a trifecta in a state, they can run fairly far with gerrymandering, at least until court intervention becomes inevitable. State governments with split partisan control often see least-change proposals, those that vary slightly from the previous decade’s map. Such results arose in 2021 in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania.

Partisan control of state courts can also help in allowing a gerrymandered map to stand, although not prohibitively so. Again, New York’s Court of Appeals, all seven seats of which are held by Democrats, ruled that the state legislature’s congressional map was a partisan gerrymander.

What to Look for in a Gerrymander

Some think that while odd shapes and boundaries are enough to warrant a claim of gerrymandering, this isn’t always the case. However, it can be a start. Racial demographics, cracking/unpacking of urban areas, and noncontiguous boundaries are often the telltale signs of a classic gerrymander. New York Democrat’s 2021 proposal featured a noncontiguous NY-03, which stretched from Setauket across the north shore to Queens, jumped the East River into the Bronx, and trailed up the river banks to Westchester. Since the district was noncontiguous – as it crossed a body of water – it was one of the several nails in the coffin for the map.

Efficiency Gap – This defines a party’s “wasted votes,” those that do not receive representation based on the results, divided by the total number of votes. The logic is that any vote for a losing candidate is considered “wasted,” as well as all the votes cast for a winner that exceed the minimum to win the election outright. For example, if Democrats cast more votes overall in a state’s congressional elections, but Republicans walk away with more seats, the “wasted votes” benefit the Republicans, as Democrats are concentrated in areas where their votes simply didn’t go as far. High efficiency gaps are not necessarily signs of an unfair map, but it can be a basis for such claims.

Median Seat – This is the difference between the partisan lean of a state and the state’s most “middle of the road” seat. A state’s overall lean can easily eclipse a state’s most competitive seat, which would not prove an inorganic map, but if a state’s median seat is far off from the state’s overall lean, it could indicate a map tilted to a party’s advantage.

Competitiveness – Somewhat counterintuitively, a state’s overall number of competitive seats is not often considered a threshold for a fair map, as a maximum number of competitive seats might violate the Voting Rights Act and/or other laws that require districts to accurately represent the electorate.

Current Examples of Gerrymandering

The 2020-2021 redistricting processes across most states that feature competitive districts saw contentious processes, with many resulting in litigation. The hyper-partisan era the U.S. currently finds itself in was certainly embodied across the country.

Democratic Gerrymanders – Although the New York map failed, Democrats passed an aggressive gerrymander in Illinois, as well as tilted maps in New Mexico and Oregon. In Illinois, Democrats pit two incumbent Republicans against each other, axed a Republican district after the state lost one after the Census, and aggressively drew three competitive seats to their distinct advantage. Democrats also “unpacked” areas of interest in Nevada and New Mexico, creating scenarios in which strong Republican environments could sweep all seats, but also environments in which Democrats could retain them easily. This happened in 2022 and saw Democrats oust New Mexico’s only congressional Republican.

Oregon gained a new district after the Census. In addition to shoring up OR-04, the new OR-06 was made markedly blue, although 2022 hosted a close race. OR-05 was won by a Republican, but remains a frontline seat for both parties this year.

Republican Gerrymanders – Republicans went on defense and shored incumbents’ prospects in Texas, Indiana, Georgia, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Utah. Republicans could have been more aggressive in Texas, but allowed Democrats in competitive seats to face easy re-election campaigns instead. The other states saw Republican prospects rise in one seat each.

Republicans went on the offensive in Tennessee, North Carolina, Florida, and Ohio. North Carolina’s map was struck down and replaced with a fairer map in 2022, which saw Democrats flip two seats. Republicans redrew the map last year, which has resulted in litigation, but likely not in time before November. Kathy Manning (D, NC-06), Wiley Nickel (D, NC-13), and Jeff Jackson (D, NC-14) all chose not to seek re-election due to the harsh nature of the maps. NC-06 features no Democratic challenger, virtually guaranteeing a Republican flip.