What makes a certifiably good film?

You could argue it’s a combination of directing, acting, writing, plot and score, or you could just say that it’s the message the film contains that qualifies it as a “good” film, all other characteristics excluded. Then, there’s the angle that if it holds up over a significant period of time, it can be considered a great piece of art.

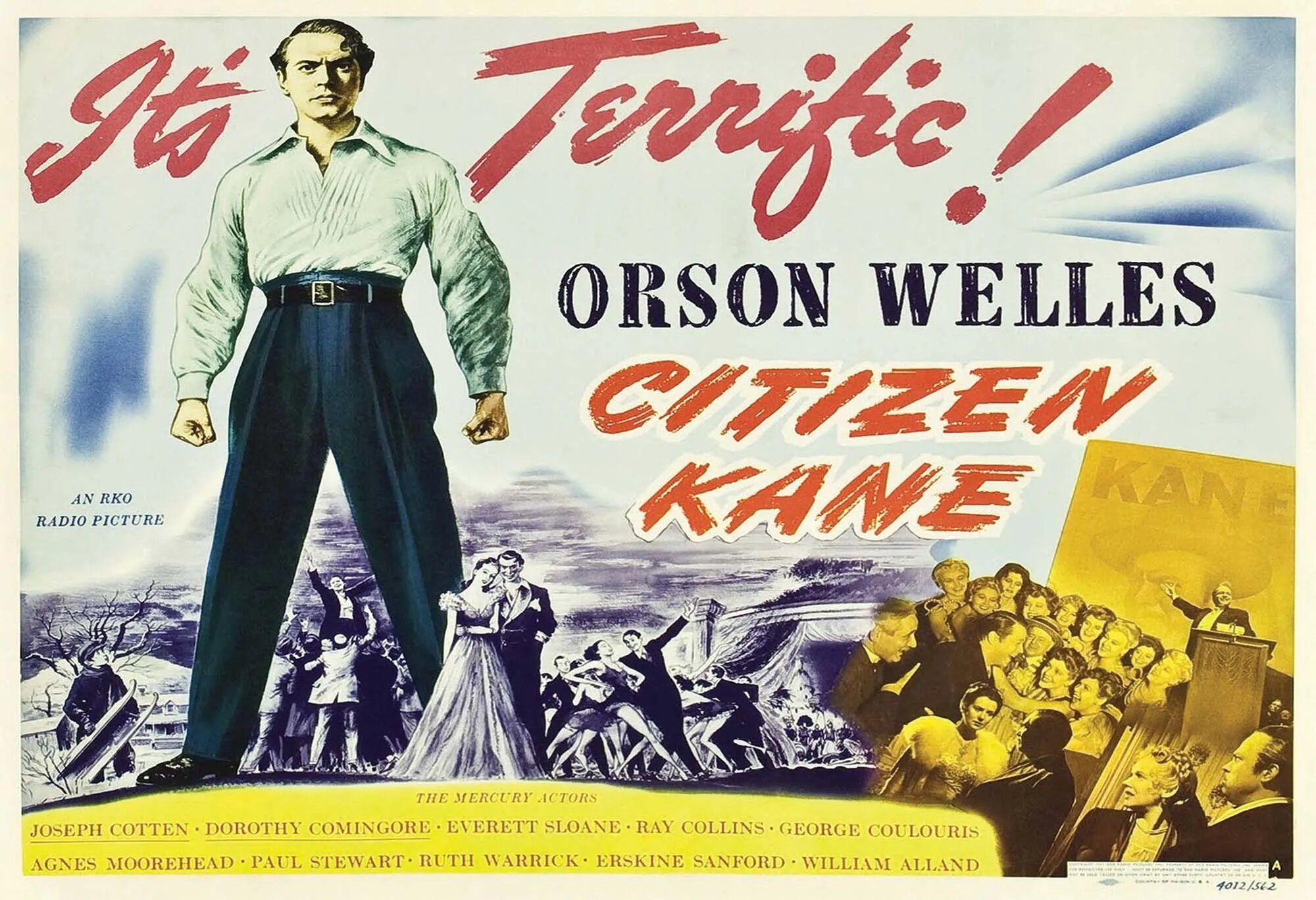

Orson Welles’ 1941 masterpiece Citizen Kane checks all of those boxes, and likely any more that you can come up with.

While critics have hailed it as one of the best, if not the best film of all time for decades, it’s still a massively difficult task to declare a single film the greatest. Based on the aforementioned criteria, we could probably fit that title on dozens, if not hundreds of other films.

This task is also uniquely complicated when viewing our place in the entertainment timeline. In a world of endless content via streaming, indie projects, and even YouTube, the allure of the cinema has somewhat fallen by the wayside. No longer will generations have the massive common ground they used to.

Because today’s consumers are not bound to a set number of channels or governed almost completely by the anticipation of release day in the theaters, everyone is completely spread out. Add the fact that people can watch literally whatever they want, it just adds to the fact that the general public is simply not on similar wavelengths as they used to be.

So, with all this in mind, it stands to reason that if a film made in the middle of World War II still finds itself relevant in the age of several streaming services, it truly must be able to withstand the test of time and fulfill decades-long hype.

And deliver it does.

The film is loosely based on the life of businessman, newspaper magnate and politician William Randolph Hearst, of whom it is also something of an open mockery. The New York Journal owner, yellow journalism connoisseur, twice-elected Representative to the US House and failed candidate for Governor of New York in 1906 tried desperately to impede the production and release of wunderkind director Orson Welles’ first film, Citizen Kane. The film was not met with immediate success due to a small number of theaters that ran limited screenings.

The film opens with a long, panoramic look at Xanadu, a large mansion on a massive, lavish property, based off Hearst Castle in California. The mansion used for some exterior shots of Xanadu was actually Oheka Castle, located in Huntington.

Mysteriously, an old and dying Charles Foster Kane utters his last word: “Rosebud.” The movie then introduces a reporter charged with finding the meaning of the word. Most of the film is told in flashback, as the reporter tracks down and interviews some of the most important people in Kane’s life, such as his ex-wife, his former boss, and his best friend.

Kane is a man who was loved and hated, sometimes by the same people. He has everything, yet he learns he has nothing. It’s an archetypal tale, but one delivered with a fresh sense of passion and innovation. The brilliance of Welles’ storytelling makes it even more impactful than several other retellings of the same idea.

Throughout the flashbacks, we learn Kane is a rags-to-riches child, thrust into success with a fortune that turns him into a newspaper executive. His power and fortune quickly fuel his ego and arrogance. Hearst’s delve into politics is loosely covered in the movie, with Kane losing an election for Governor. Some recent comparisons between Kane and Donald Trump actually hold up, with Kane pledging, if elected, to form a committee to investigate the corruption of his opponent.

Some things never change.

Convincingly, Welles gives us a look at a man’s entire life in just two hours. Flashbacks that overlap from multiple characters’ perspectives change based on those perspectives, as reality would have it. The amount of detail crammed into the movie warrants several rewatches, essentially making it a cinematic onion: the more you peel, the more you reveal. Without explicitly spoiling, the “Breakfast Montage” shows exuberance of young life, followed by rapid aging and a slowly deteriorating marriage, all within five minutes. The scene is also decorated with tiny details you’ll have to watch to catch.

It’s truly remarkable how much emotion, detail and depth Welles gives us in such short amounts of time. The twist ending is enough to live with someone for years, and while it may not immediately hit the viewer, the more one chews on it, the better it gets.

However, the picture was more than a telling of a complicated man’s life. It is still regarded as one of the most pivotal moments in cinematic history. Welles, then just 25 years old, pioneered some facets of filmmaking that completely changed the game. The now-ubiquitous shot of a camera panning through a window to end up in the room on the other side was specially conceived for one of the first scenes in this film. In a contentious argument late in the movie’s production, Welles insisted on cutting out a part of the stage to lower a camera into it for an exceptionally low angle.

Long, contiguous takes, dynamic lighting, angles, and shadows, as well as robust storytelling made this film an instant pioneer of American cinema.

The film is also brilliantly scored by Bernard Hermann, who would enjoy a lengthy career throughout the 20th Century. He would be partnered closely with Alfred Hitchcock, scoring such iconic moments as the shower scene in Psycho (1960), as well as Martin Scorsese’s 1976 hit, Taxi Driver. Like Welles, Citizen Kane was Hermann’s first film, scoring it at 30 years old.

So, does Citizen Kane earn the distinction of “best film in history?” I personally would slap that label on it, given the amount of thought, depth, innovation and lasting impact this semi-biopic-turned cautionary tale still imparts. Many quotes from the picture are sure to have a lasting impact as well.

Whether or not you would assign it the same distinction I do is for you to find out.

“I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life.”