We’re about two weeks out from Election Day, and I’ve released a couple of pieces centered on Lee Zeldin’s path to Albany.

First, I discussed the history surrounding New York politics, the benefits and drawbacks of each campaign, and what would have to continue in order to see a Republican elected governor of the Empire State for the first time in 20 years. Then, last week, I discussed the polling and demographic trends toward Zeldin (R-Shirley) and how a real race has been materializing.

Now is the time to get granular with the numbers and dig into what exactly would have to go right for Zeldin to win, and with the recent polling information we have, it’s actually not as long a shot as some might think.

A model I’ve been building draws comparisons from the 2018 Governor’s race, as well as quantities and percentages of registered voters across the state, in addition to current trends and the national environment. Briefly, what happens in New York is probably going to be mirrored nationally and vice versa.

The major statistic all observers will be eyeing this year is where registered voters go. I’ve discussed previously how New York is an “elastic” state, despite not being a swing state or battleground state. A state’s high elasticity is attributed to a substantial portion of registered Independents or nonpartisans; in New York, Nonpartisans are referred to as “Blanks.” So, while Democrats have won consistently and with large margins for decades, it’s tough to say how prohibitively safe they are. Observers can be surprised to see how far the other way the pendulum swings when Blanks break from the party line. And in a state like New York, Blanks tend to vote with the party in power— in this case, Democrats.

For comparison, states like Georgia and North Carolina are considered battlegrounds (or swing states, depending on who you ask). But they are considered “inelastic.” The cause for this is high Democrat and GOP registration but roughly no middle ground. So, while there is no real “middle” to court, elections here are more about turnout among party loyalists.

Democrats account for just over 50% of registered voters in New York, with the GOP at just 23%. While Independents make up a paltry 3.5%, Blanks make up a whopping 23%, equal to the total of the GOP.

The obvious strategy: win as many Blanks as possible.

So, the basis for my model and what it assumes: Zeldin would need to see a large turnout among Republicans, anywhere from 85%-90%. While this seems like a tall order, keep in mind that in 2018, when compared with the county-level vote totals and crossed with statewide party registration, the GOP turned out almost 20% more than the Democrats.

However, this does not account for who courted more Blanks. Reports show that Democrats won Independents by 13% in the 2018 House popular vote, so it’s not wild to assume that Governor Andrew Cuomo attracted around Blanks by about 10 points, given three House districts in New York flipped. I did find that there were eight counties where Molinaro’s vote total was greater than that of the GOP registration for those counties, meaning he won considerable crossover support for himself in some areas.

So, with GOP turnout higher in 2018, it’s not a huge stretch of the imagination that Zeldin runs ahead of Molinaro, especially in a high-turnout, ostensibly good GOP year.

The next assumption: Zeldin wins Independents and Blanks by 60%-40% each.

This is a much taller order, although not off the table. Recent polling has shown Zeldin winning these groups by as high as 20 points – as per the Quinnipiac poll – and as low as 9 points from other pollsters.

Bear in mind: Zeldin can still win Blanks handily and lose the election, so he will need at least a 15–20-point margin among these voters to even have a shot.

The next assumption: Democrat turnout hemorrhages at around 60%.

This is a bold assumption, but one that needs to be made. Registered Democrat turnout in 2018, according to my model, showed them at 62%, and that was in a good blue year. Combine that with the fact that it’s tough to find data on where Blanks swung that year, and we can assume that registered Democratic turnout was lower.

We can play Devil’s Advocate both ways and say that even in a strong blue year, Democrats still didn’t turn out big. We can also say that the race wasn’t competitive– therefore, the need for turnout was lower.

No matter the spin, Hochul needs more than 60% to insulate herself against Zeldin.

Polls have shown an enthusiasm gap largely benefitting the GOP nationwide this year, especially Zeldin in New York, with 80% Republicans and Independents “highly likely” to vote, with Democrats at a mere 60%.

The final assumption regarding sheer vote totals: Zeldin must find a net gain of 10% in crossover support.

It’s largely common for politicians to see about 10% of the opposite party prefer them in a head-to-head matchup. Where those intentions fully lie remains to be seen on Election Day, but this is familiar territory no matter what level of government you’re prognosticating.

Polls have reflected that same idea: Zeldin can be assumed to take 10% of the Democratic vote, while Hochul can possibly rely on 10% of the GOP vote.

The problem for Zeldin: that’s not enough. He would need to outpace Hochul in crossover support by at least 10-15%. This is probably the tallest order Zeldin has to fill this race. Polling has shown him hovering around 10%, but if voters have second thoughts at the ballot box, this particular group of the electorate can give us a surprise. Longstanding Democratic NYC Councilmembers’ endorsements of Zeldin might be the light at the end of the tunnel for Zeldin and the proverbial canary in the coalmine for Hochul.

My model shows 10% of registered Democratic votes for Zeldin is about 600,000. It’s not much when we’re discussing an election that could see a total turnout of 9 million votes, but for Zeldin, a margin of victory will be well below that 600,000-vote threshold.

Again, we can play Devil’s Advocate, assume the national environment and key House races help Zeldin take a low-double digit portion of the Democratic vote, while Hochul probably only takes a mid-single digit share of the GOP vote. Given that there are much fewer GOP votes to siphon in New York due to the large registration disparity, I’m comfortable with those figures evening out to what Zeldin would need to win.

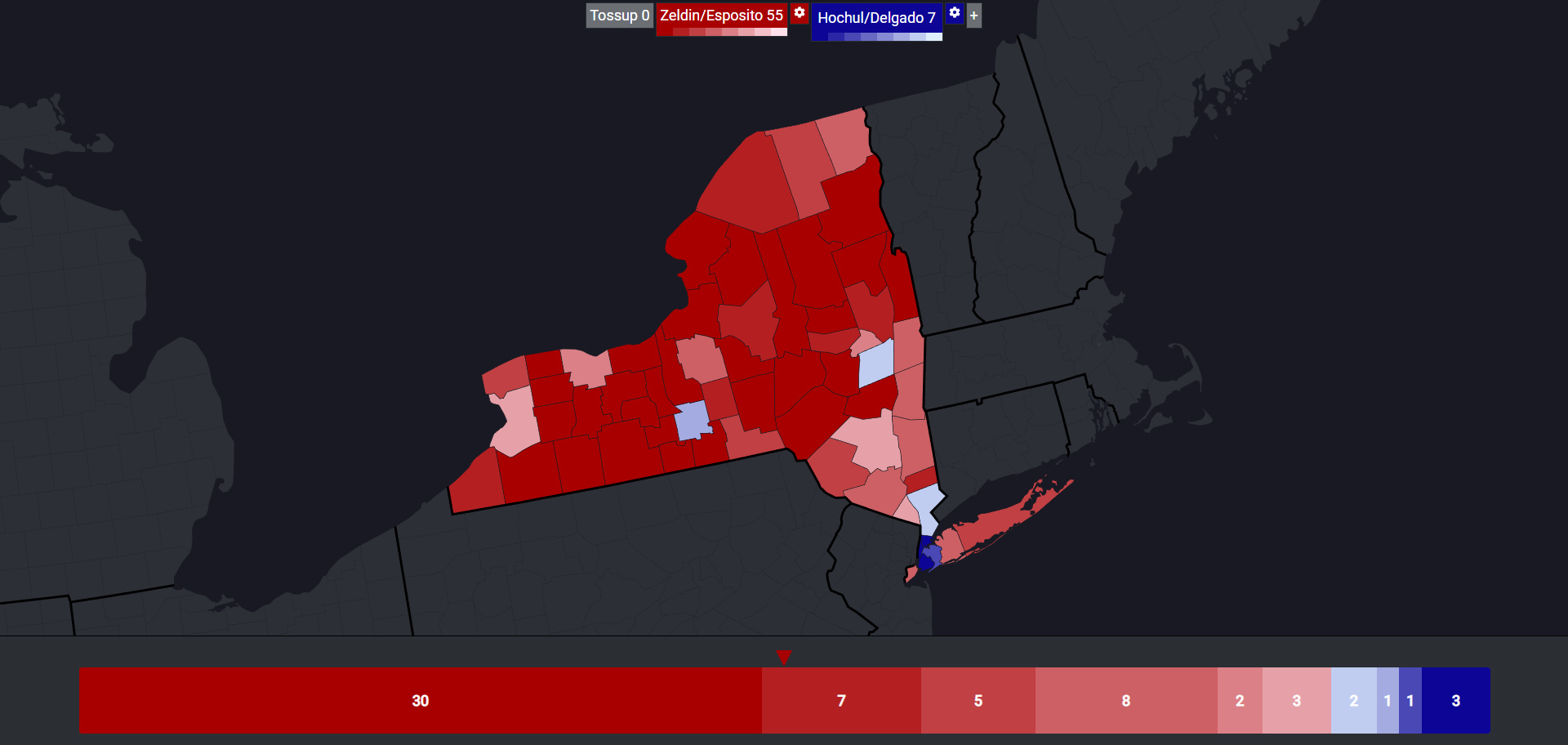

Lastly: the map. My model considers county-level swing with these statistics. If all of these numbers fall into place, Zeldin could win 55 of the 62 counties, including narrow margins in Erie County (Buffalo), Monroe County (Rochester) and Onondaga County (Syracuse). He’d also flip Nassau, Rockland and Ulster Counties and hold Hochul to single-digit margins in Albany and Westchester Counties.

Zeldin would also need max turnout ancestrally-Democratic areas, such as the North Country and Hudson River Valley. Molinaro did well in these areas, so Zeldin has some ground broken already.

Finally, Zeldin would need at least 30% of the vote in NYC to cut into the lion’s share of blue votes. Recent polling has shown him hovering from 33% to 37%, indicating this is a realistic possibility. Queens would likely see the largest swing of the four Democratic Boroughs. Despite Curtis Sliwa’s (R) resounding defeat in the 2021 NYC Mayoral Election, he outperformed typical Republicans in certain parts of the city, namely among Asian-American communities. Zeldin has some groundwork laid for him.

Now, he would just need to take it home.

All said: if my model, predictions, maps and gut are correct, Zeldin would win by a 0.68% margin, or by just 63,782 votes.

Obviously, there is little to no wiggle room for Zeldin here. I’m confident in these numbers and think it’s absolutely plausible these shifts can occur, but if anything shifts in Hochul’s favor by just one or two points, she would narrowly win under these circumstances. While all of these feats are, in and of themselves, not massively difficult to pull off, it will be difficult for the perfect storm to coalesce around Zeldin on the same night.

With two weeks out and no “October Surprise” having been delivered yet (in my opinion), a lot can happen. Any politically adept citizen knows that two weeks is a long time during an election rush.