Say it ain’t so, Mal.

Twelve years ago, on July 16, 2010, a cinematic visionary reminded us – to the impressive tune of eventually $836.8 million at the box office – that we create and perceive our worlds simultaneously.

Christopher Nolan (Memento, Interstellar) has a complicated mind. Though a singular talent of the visual medium, the British-American 5-time Oscar nominee is admittedly nothing without his team. So much so, he compiled a darkly dreaming, cathartic exorcism of his, of everyone’s, foremost sleep paralysis demons at the spinning top of last decade.

He achieved this through exploring a unique narrative terrain better known as the nexus of one’s inner universe. With Inception, Nolan set up shop where a “love letter” framing device meets the execution of a timeless subgenre: the “one last job” heist caper, wherein the broad mission, in good-old Wizard of Oz fashion, is doing whatever it takes to return home.

Nolan cited the “write what you know” mantra, and the support system he’s most tangled with – film crews – as imperative to the development of Inception’s principles. At the time, he told Entertainment Weekly there is a lot of himself in the “team-based creative process” endeavor’s protagonist, Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio). “Getting lost in dreams” [like Cobb] is something Nolan says he regularly experiences while on the clock alongside those who help him see his grandest film fantasies realized.

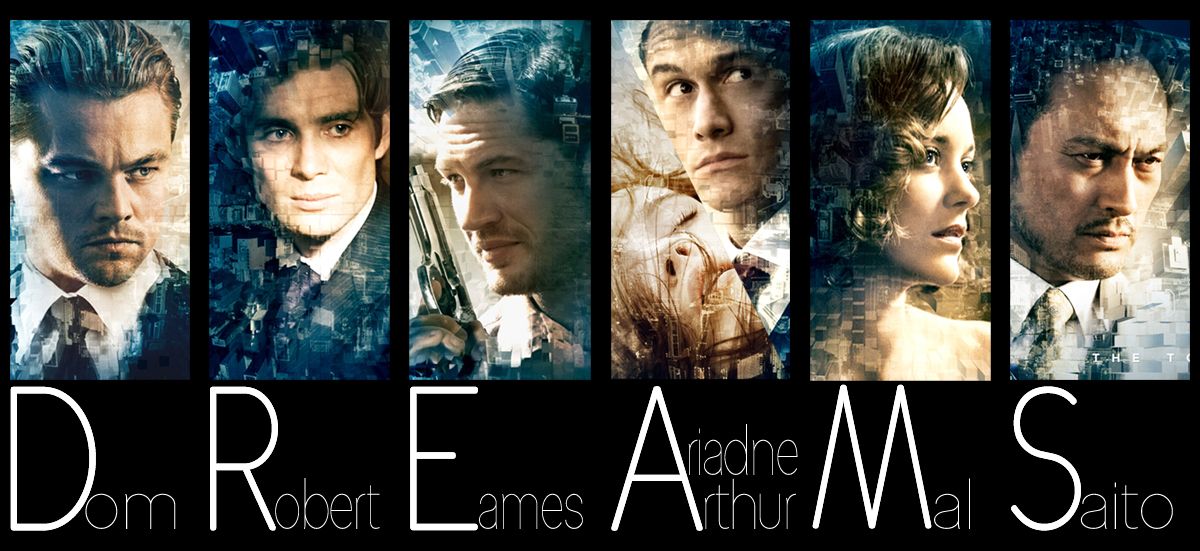

As the allegory posits, beyond heist team leader Cobb – whose outfit’s ultra-specific skill set, information extraction by way of dream infiltration, is something out of a Philip K. Dick novel – representing Nolan / “the director,” Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is the right-hand confidant, or the “producer.” Ariadne (Elliot, then-Ellen, Page), is the architect, or “screenwriter.” Per Escapist Magazine, master forger Eames (Tom Hardy) is the actor, “a chameleon who brings the work to life,” and Saito (Ken Watanabe) – who hired the ‘Imaginative Five’ in exchange for Cobb’s criminal charges erased upon the job’s completion – is the studio that’s “final future depends on return on substantial invest.” Lastly, Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy) is the audience, which Cobb and company – and Nolan and his as well – must compel to dream a dream they conjured up, and make them (the subject) think was theirs all along.

Commissioned to reverse-engineer their usual methodology and perform “inception,” the implanting of an idea into someone’s mind, the same-named film quickly becomes a commentary unto itself. In a disbelief-suspended present where one’s peers can follow them in and out of a shared dream space to break up the echoes of a subconscious projected, one can just as easily pursue confronting, and then defeating, the string-perverting face of the subconscious in all its scheming glory.

For those still in need of a rewatch, Inception is like that sometimes overwhelming dream you still can’t quite interpret. Despite such, you never waver, with your intrigue intensifying each time you recall the ambitious misadventures of your uninhibited nighttime alter ego. For even though something may not have been fully understood, this does not for a second suggest it was devoid of possessing an entertainment-certified scarlet “X” factor.

Since Cobb’s subconscious is manifested as Mal (Marion Cotillard), his once “lovely” but now a most menacing warped memory of his deceased wife who haunts his every sleep-set movement, the runaway dreamer recuses himself from dream-designing. Confrontation-weary despite the built-in jack of his trade, Cobb resembles the up-against-it director, a less-assured “Bizzaro World” Nolan, in that his players can’t help but put him down when he’s not in the room.

With insecurities therefore viscerally rampant in a playground where the ground is time and its players are regret, Cobb appoints Ariadne to essentially do his dirty work. In Cobb’s eyes, a layout laid out by someone else is the quickest path for him to purchase his last-ditch ticket home to his two children. He has been separated from Phillipa and James since his reality-disillusioned wife framed him for her murder by free-fall jumping to her demise. To Mal, this was less a suicidal act than it was a leap between dream levels–the fatal price one pays when they abandon their “constants” by the wayside.

Inception busted the block despite no souvenir “totems” finding their way into McDonald’s Happy Meals, no wardrobe iconography transformed into Halloween costume fodder, no knockoff “dream kits” sold in retail. Between Dark Knight installments, Nolan instead plunged into the free-wheeling abyss of a not-forkids exercise. Even still, Inception’s adult audiences are made to feel as vulnerable as the kids they once were, and still are at heart.

The film also propagates the true-to-life notion that when sensitive information is buried within, it’s vault-kept in what our waking selves register as agents of protection – anything from a safety deposit box to our grade school locker that’s combination inopportunely, but understandably, escapes us. The personified subconscious’ role – namely, Mal’s “modus operandi” throughout while facilitating her deep-in-mourning husband’s endless state of restlessness – is to be as much of a guide as they are a gatekeeping foil. Mal is the wicked witch of grief who can lead this wounded horse to water, but only he can make himself think [unless he’s been incepted, of course] of what he’s lost, and how it can be found.

Just like your last nightmare-fueled brush with slow death, Inception maps start to collapse when the unknowing dreamer realizes they are dreaming. Within the film, and in life, a rule of thumb is to never undermine the authority of the subconscious, as intimated in Forbes’ breakdown on how training your subconscious helps yield results. If you reject it mid-slumber, you will face the wrath of explosive termination in the crescendo between dreamscape destruction and literal awakening. For Nolan, what started as a high-concept horror ended as his decade-in-the-making Inception investigation: the furious case of his early-formed obsession with the middle plane between this loaded pair of dice come to life.

Whether you’re an athlete, an artist, an extroverted community player or an introverted “lone wolf,” or someone belonging to another circle entirely, you can bask in the beauty of Inception’s staunchest messaging. Even when we think we’re alone, we simply are not. Just around the corner, there is a qualified team of exceptional individuals waiting to be let through your door. Through any door. We may be the pilots of our own lives.

We may be the architects of our dreams. We’re the products of our pasts, too, while resisting the crutching allure of being exclusively beholden to them. And, perhaps most evidently, we are the company we keep. So don’t surrender to your subconscious when pressed to, because it’s not the filmmaker; it’s the film critic. Tell me: what self-respecting creator ever tailor-made something for “two thumbs up” rather than a whole house brought down?

Meanwhile, you’re not only the director of your story, you’re where the art begins and ends—the art incarnate, as Inception contends well past the closing credits. Thus, you should accept the subconscious’ boldest challenges by calling all its bluffs without once doubting its existence. Do that, and you may just see the remainder of whatever hand you’ve been dealt to the other end of the epiphanic rainbow—where your whole team awaits with eager arms, ready to congratulate you on a job well done.

Inception is currently streaming on Netflix and HBO Max. Dare to dream?